Composite

Two Columbia Road

2 Columbia Road, London E2

20 to 25 September 2011

“Composite is both verb and noun, an action and an outcome, a process and a finished product. Within it are roots and hints of other words — compose, composition, posit, position, site and compare — all of which relate to art, architecture, fashion and design. This exhibition brings together a disparate group of creatives who’ve crossed those borders, gone beyond all comfort zones. Often working in collaboration, they’ve mutated their practice to produce hybridised, surprising solutions.

Questioning traditional processes, reusing discarded materials, exploring overlooked technologies, composing disparate elements, exposing the artificial, celebrating the mundane; these are just some of their tactics. The end results, the works on show, are diverse but they share two things in common, a degree of intricacy and ‘a way in’. They’re not exclusive, instead we’re encouraged to engage and play, inspect and manipulate, delve and re-arrange. Complex, interactive, considered, non-precious; this work is of its time. We live in a composite world.”

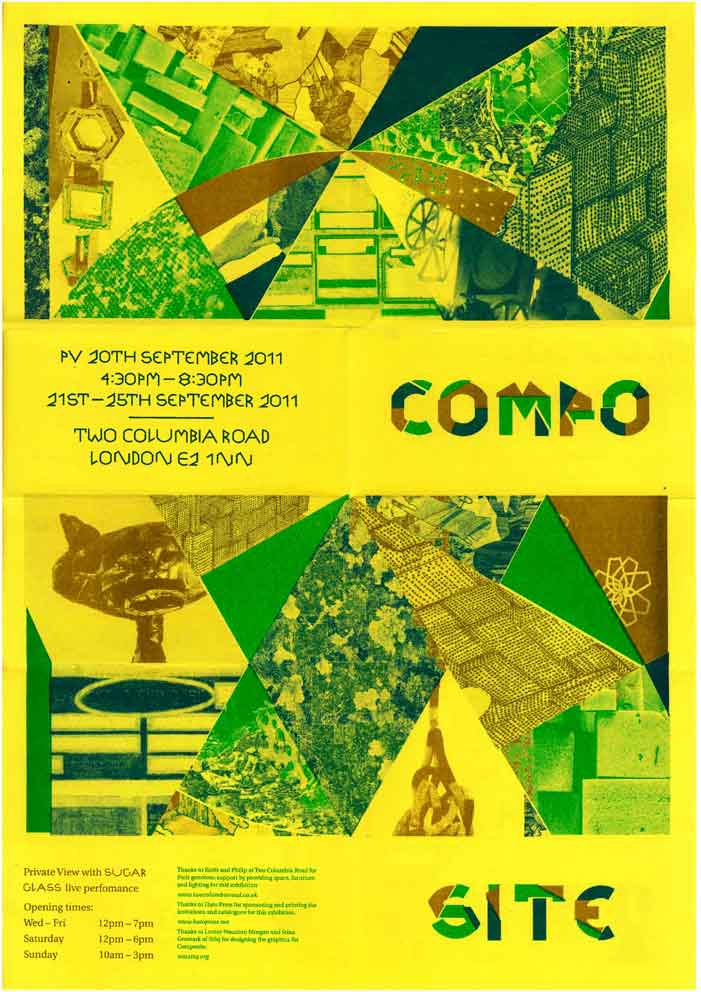

I wrote that text for the reverse of a fold-out poster, above, alongside first-person biographies of contributors and short explanations of projects, for a small group show in the back room of a vintage furniture shop in East London. The poster folded into a booklet and the text, which I’d describe as a partial exploration of the word “composite” in the context of creative practice, was also displayed as a wall panel. Composite could best be described as a “fringe event” to the mainstream London Design Festival (LDF) 2011, although there was no ideological reason behind the project being fringe. The show came together after the deadline for inclusion in LDF’s printed guide, but because it had no dedicated website Composite is now almost invisible, existing under the (Internet) radar and predating the proliferation of social media that now guarantees longer-term presence. Google it and you’ll find minor mentions on the main protagonists’ websites; a nice review of Bethan Laura Wood’s jewellery on Amelia’s Magazine, here; and an archived post by Dan Rubinstein on design blog Sight Unseen, here, which mainly concentrates on the party f(l)avours, Fernando Laposse’s yummy Sugar Glasses, and credits me as “curator”. In effect, I was a sounding board for Bethan’s initiative and project manager for the publicity and publication, both roles that fall within the remit of a curator.

Composite featured young designers and image-makers whose careers have successfully developed over the intervening years; alongside Bethan (interviewed, here) and Fernando’s contributions, there was also Fabien Cappello’s semi-permanent shelving, mysterious drawings by Gary Card, an unruly chandelier by Silo Studio, Jez Tozer’s personable fashion photography and graphics by Louise Naunton Morgan (including a bespoke typeface with Stina Gromark as StSq). The show was small-scale and spontaneous, demonstrating how informal contacts within a local scene can spark a creative initiative. And although all the exhibitors are canny social media mavens, this little show is now “beyond the archive”. Previously on this blog, I’ve explored the sad fate of pre-Internet-age activity, here; to be invisible is to be irrelevant. Such treatment is meted out to any activity, whatever its date of inception, if it is under-documented online. With the security and longevity of archives under threat, as mentioned in a previous post about digital history, here, perhaps the safest option is to digitise as much material as possible.

Why am I re-posting this now? As I organise the mass of material collected during my doctoral research, e.g. ephemera relating to hundreds of museum visits, gallery exhibitions, talks and events, I came across the poster for this show. Coupled with the fact that I experienced this year’s LDF only virtually, and mainly via social media, I began piecing together recollections of previous events. LDF started in 2003; in 2009 the Victoria and Albert Museum sanctioned the initiative by becoming its “hub”. Our fringe event in 2011 was conceived by creative collaborators who recognised the importance of having a “presence” at LDF, comparable to participation in the design world’s annual major jamboree, April in Milan.

London Design Festival Guide 2012; cover in that distinctive red, which flags LDF events around town.

By LDF 2012 I was working on my doctorate and keen to understand how a museum might build communities of diverse audiences via events and participation. The V&A’s hub-function looked to be an interesting test case and I opted to spend time in and around the Museum for the duration, to experience the atmosphere and events while paying particular attention to fellow visitors. Apart from the invitation-only parties and a pricey conference, most of the events were free and accessible but often required pre-booking (I booked two via the V&A’s very cranky online ticket office). Talks and workshops were concentrated in the Sackler Centre (lecture theatre, seminar rooms, dedicated classrooms), while tours, gallery talks, displays and installations were spread across the entire Museum. The LDF guidebook for 2012 lists 52 one-day events at the V&A; an additional fold-out map pinpoints 38 interventions within the Museum (although the map contains two typos, which makes it read as 36) and 13 of those have longer, explanatory captions printed on the map. Apart from that information, I recall seeing two large posters, on display at the entrance to the Sackler Centre, listed (literally) hundreds of events, so only a fraction of what was on offer appeared in the guidebook. Neither were all these listed on the V&A website, nor LDF’s website, which also had a separate ticketing arrangement for some events. So, there was no comprehensive source of information or access for all the events on offer. Despite the unnerving sense of, “what have I missed?”, a little chaos can be serendipitous; because of the concentration of events, one cancelled talk might create an opportunity to wander into another room and into another event that might have been overlooked. The Museum was buzzing, full of busy, motivated visitors looking for particular events, guidebook in hand; and it was obvious that they had high expectations of the Museum.

One event from that year that provided unique insight into the organisation and aims of LDF was actually held at the British Council.

Design Festivals Round Table

Prince of Wales Suite

British Council

10 Spring Gardens, London SW1

20 September 2012

Part of the Design Connections initiative organised by Evonne Mackenzie, and written up on the Architecture Design Fashion (ADF) team’s blog, Back of the Envelope, here. This ongoing initiative facilitates privileged access to the LDF for museum and gallery professionals with a particular interest in design, and in its first year delegates included: Olwen Moseley, Director of Cardiff Design Festival; Babitha George, Co-founder of UnBox Festival Delhi and Eric Zhu, Chair of Graphic Design China. This breakfast event (ticketed by Eventbrite) teamed Sir John Sorrell, Chairman of London Design Festival with (let’s call him “design guru”, why not…) Wally Olins.

Discussion focused on to the proliferation of design festivals, as the annual global tally nears 100. As it was the tenth anniversary of the genesis of LDF, co-founder Sir John Sorrell provided a potted history. The idea had been brewing since 1994, when John was Chairman of the Design Council, but by 2002, at the Theo Crosby Memorial Festival at the Globe Theatre, John recalled being told, “put your money where your mouth is”. After a year of planning, LDF launched in 2003 with 40 events and 20 partners. “We looked at other design festivals and no one was doing what we wanted to do; we wanted to use the city, London, as the stage”. That meant, not hosting events in a shed, like a trade fair, nor in an auditorium as a conference; instead the aim was to generate and inspire events across the city, in effect, fostering a DIY attitude by persuading people to take the initiative. By 2011, LDF included 300 events staged by 100 partners, with 350,000 visitors (30,000 from outside the UK) and generated the largest weekly attendance figure in the history of the V&A (at least since they’d started counting). A media campaign, beginning with a launch in March, generated over £2.5 million worth of coverage via 100 media outlets. John described the role of the LDF organisation as “co-ordinating, encouraging, promoting, making it happen”. With the help of another design knight, Sir Terence Conran, the Foreign Office became involved, and larger institutions have come on board as working with galleries and museums has become high priority. John explained: “Every design festival city is different and it has to be appropriate to each city; the reason it works in London is because it’s a city with a multi-disciplinary and multi-national design industry, where every design discipline is practiced”. LDF has counted 48 design disciplines including architecture and fashion, and 46 were represented in LDF events in 2012.

Wally brought up the issue of funding and wondered if it might dictate LDF’s offer? Speaking from the audience, I questioned if there might be a political angle to accepting funding from certain organisation by asking if the Greater London Authority (GLA) was a strong(-arm) partner in the proceedings? John answered that the GLA was interested in the impact of LDF on London’s economy and had provided funding, but it was a small percentage and came directly from the Mayor’s office. But more than the money, he stressed the importance of building trust; “if you have the right relationship, you can get permissions, they can waive planning laws, and we can get things done, but they have never asked us to do anything specific”. Later John added that it is crucially important that government is not a major funder because financial cuts (or a change of regime) could kill off any festival that was too dependent on one source.

Informative as that event was, another LDF event fundamentally questioned the role of design both within and beyond the design industry.

The Role of Design in an Era of Crisis

Sackler Centre

Victoria and Albert Museum

Brompton Road, London SW1

19 September 2012

Run by Jody Boehnert of EcoLabs, a visual communicator “designing for emerging ecological perception”, the workshop discussed “design versus the design industry” and the integral role of Occupy Design in the Occupy movement. A pertinent question was raised; how did this event fit into LDF? Speakers and audience were asked to create teams, to workshop ideas and and offer feedback, which went something like this: it’s a new conversation, let’s keep it going and make it the norm; make design more accessible to the public; design should be radical and transparent, we should know the real value of a product and how the profits are shared; we need a Designers’ Union like the First Things First Manifesto (which was a comment on the advertising industry by graphic design professionals); we need to eat and talk and exchange ideas and skills so as to educate each other, and we need a space to do that in, a SAFE SPACE; we need to sell stuff and barter and partner with entrepreneurs; we need a worker’s network to protect interns and graduates; designers need to challenge the profit motive, create co-ops and new schools; Occupy can speak for design, it was suggested, but not for the design industry, so we need a hub (yes, that word was used) to create profile within the design industry and highlight designers who work for social good. A final checklist, distilled from all the group discussions included these statements: keep your integrity; lobby government; empower local communities by finding and solving local problems; forget grand statements, instead, lots of little changes will eventually add up to big change.

It was inspiring and positive to be part of such an event, hosted by the V&A and prompted by LDF. My final take away from it was that a design festival can be all things to all people, fulfilling LDF’s facilitating model, but that to continue to build on such enthusiasm there needs to be regular events in a fixed venue, although perhaps not as formal as a museum space. University of Brighton’s Professor of Design Culture, Guy Julier, instigated the Design Culture Salon at the V&A, which tackles a different topic each month and is now in its fourth season. A panel of experts give short positional statements before a Chairperson invites the audience to ask questions. The format shies away from presentations and the lectern but the audience can be reticent. By contrast, at Jody’s “workshopped” event the large audience was divided into smaller groups, and despite initial murmurs of “what shall we talk about”, the non-hierarchical grouping was less intimidating and stimulated conversation. That said, the continuing popularity of the DCS has turned the V&A into an all-year-round “hub”, so that beyond the remit of LDF it has become a place for conversations about the role of design on a bigger stage. But, as Sir John Sorrell pointed out, design is a broad church, and there could be more spaces for more talk. Beyond informing the public about what’s going on in the Museum, which is a major task in itself, the process of documenting and archiving the mass of outputs, not only generated by the LDF but throughout the year, is a challenge yet to be met. If designers want to keep talking, they will want to know that they are being listened to.

Screen Shot from V&A’s website found by Googling “LDF V&A 2012”; this page archives displays and photos from that year’s design festival.