Furniture: Jerwood Applied Arts Prize 1999

Jerwood Charitable Foundation

Crafts Council Gallery

441 Pentonville Road, London N1

26 August to 3 October 1999

I wrote an essay for this exhibition catalogue (produced by the Jerwood Charitable Foundation and the Crafts Council, designed by Pentagram) while I was a nomad, living and working between two continents. I remember the irony of writing about furniture when all I owned was in storage, but I was an unrepentant collector, even buying pieces from fellow students while at the RCA (Allison Jane Thomas’s Tutti-Frutti stool (1990) is in the V&A; mine is upholstered in tan leather).

Coincidentally, 1999 was when auctioneer Alexander Payne first coined the term Design Art; he later ditched it due to “misuse” as reported in ICON (8/2/08). So, when I say in the essay, “furniture has no pedestal”, that was about to change, although the turn towards narrative and meaning beyond function was acknowledged.

Another shift of emphasis has occurred in the career trajectories of new designers. Where I listed migration to Milan, the epicentre of the contemporary furniture trade, as a right of passage, subsequent diversification of production has widened the geographical spread of design activity. “Eleven years ago UNESCO launched the Creative Cities Network to recognize cities around the world whose creativity has an impact on their social, economic, and political development”; Business Insider spotlights 16 design-focused cities, here. Through a mix of city council initiatives, the presence of museums and universities (with students travelling to study and then relocating), and Design Festivals and Biennales that disperse the power of promotion, designers are living and working beyond the industry’s powerhouse cities (Milan, Paris, Tokyo, New York, London), in places like Oslo, Cape Town, Istanbul, Los Angeles and Hong Kong. Hints of that trend were evident in the career choices of the designers selected for this award, perhaps because they foregrounded making in their practice as opposed to mass-production. The shortlist featured Jane Atfield, Robert Kilvington, Mary Little, Michael Marriott, Guy Martin, Jim Partridge, Simon Pengelly and Michael Young.

I’m re-posting this essay because I can find no trace of it online. It’s telling that no website URL was included in the catalogue, for the organisers or venues. In 1999 the world was on the cusp of a digital communications revolution. Where I had used fax and couriers, I was beginning to work by email. Few galleries had websites, and if they did those “early” versions were likely to be ditched by webmasters hungry for server space rather than “archived”. Today we expect to read catalogue essays and exhibition reviews online, back then print was it. That’s fine if you have access to university libraries and museum archives, but if Google is your God, the invisibility of non-digital documents can skewer research of events prior to the New Millennium. That realisation should bring into focus the arbitrary nature of online searches; all results are patchy, dependent on there being a digital trace in the first place and its preservation. I examine this issue more closely in a seminar paper (to be posted), a forthcoming book chapter and my PhD thesis.

Another reason for re-presenting this essay is to consider the impact of prizes, awards, funding and residencies on the careers of designers. In my thesis I’ll be taking a closer look at the Design Museum’s Designers In Residence initiative, which has talent-spotted a wide range of practitioners that have gone on to broker early support into successful careers. I’ve been able to trace the development of DIR (and an earlier incarnation, Design Mart) through documents and files in the Museum’s archive (a work-in-progress). DIR 2015 has just opened at the Museum, with a (timely) brief, Migration.

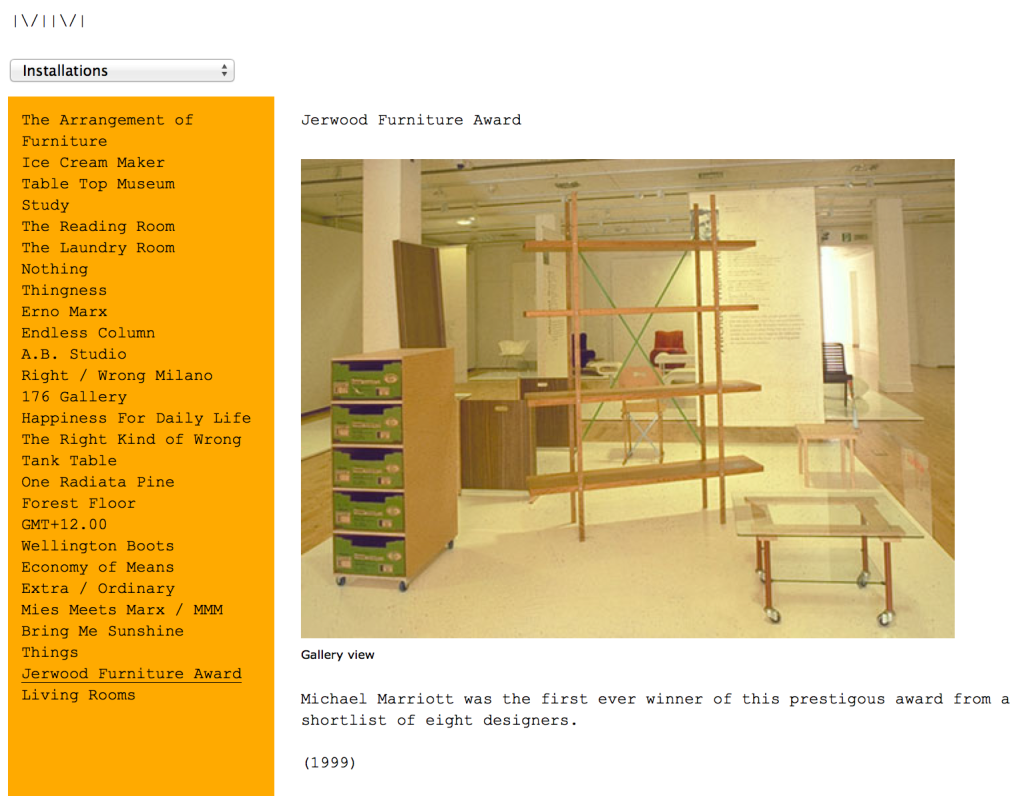

Michael Marriott was the first winner of the Jerwood Applied Arts Prize for Furniture and five years later, after the prize cycled through other craft disciplines, Barber Osgerby won the next Furniture Prize (in 2004). Marriott is now a judge of the annual Jerwood Makers Open, which presents winners with funds and invites them into the Jerwood Space gallery in London for a summer exhibition (10/7-30/8/15) and than a subsequent tour, the first leg of which has just opened at http://www.jerwoodvisualarts.org/3091/Jerwood-Makers-Open-2015–Tour-to-Plymouth/472/”>Plymouth College of Art, Devon (until 3/10/15), featuring among others Silo Studio. I wrote (another) essay for a group show they were in, Composite (2011), and nominated them for the Design Museum’s Designs of the Year (2012). For more information on the Jerwood Charitable Foundation and Jerwood Visual Arts activity re: funding designer-makers, see the Archive webpage, which traces the evolution of Jerwood Contemporary Makers (2008-2010) into Jerwood Makers Open (2011-) in PDF Press Releases; the catalogues are also available as downloads, with the earliest applied arts catalogue from 2008. There’s no trace of the Jerwood Applied Arts Prize, though, perhaps the press releases and catalogues are in a box somewhere?

Back in 1999, the partner organisation, the Crafts Council, organised the process and hosted the exhibition. At the time, the Crafts Council Gallery presented the most interesting design-focused exhibitions in London and nurtured, via commissions, an industry of 2D and 3D exhibition designers; Director of Exhibitions and Collection, Louise Taylor, is interviewed here. The Crafts Council was also proactive in supporting new makers and its Setting Up Grant was an envied right of passage for art and design graduates who qualified as “crafts people”; Google it to see pages of links to successful practitioners who started out in the 1980s and 1990s with mention of the Setting Up Grant the first entry on their CVs. The grant was intended to fund studio space and purchase equipment so makers could hit the ground running as they exited the safe space of college. But as the boundaries of practice began to blur – is it art, craft or design – funding cuts preempted any confusion about who might or might not qualify. For discussion of the boundary blur see “Dangerous Liaisons: Relationships between Design, Craft and Art” by Grace Lees-Maffei and Linda Sandino in the Journal of Design History (Vol.17, No.3 (2004), pp.207-219). The Crafts Council’s current scheme for professional development Hothouse concentrates on mentoring and training makers in the art of business at any stage of their career. Meanwhile, one way of getting over the hump of leaving college is to replicate that shared support structure. Artist-run studio spaces and “collectives” are breaching the gap; focusing on graphic design and illustration I looked at the needs fulfilled by Design Collectives, in an article for D1 Paper (2011) published by the British Council’s Architecture Design Fashion team.

The Crafts Council Gallery closed in 2006, because of the restructuring of the Arts- Crafts- and Design Councils that continued through the noughties, even as hype around the UK’s Creative Industries raged; meanwhile the business of “grant getting” expanded. There are some intimidating lists to navigate and the emphasis is on the individual to figure it out (or employ a professional grant writer). For an organisation to forge a reputation as a supporter of creative talent the results of that support need to be obvious to those applying for help. The promise of advice, mentoring and promotion, over the long-term, is more useful to “start ups” than just cold cash, because if you’re going to jump through hoops, it has to be really worth it. Building a community of beneficiaries is also a bonus for the institution: it proves that it is well connected to the creative industries; it has talent-spotting know-how; and that it can expertly manage the whole experience, to produce a positive outcome and on-going relationship. For an institution (museum or gallery) with a public programme, that legacy converts into a pool of willing participates, ready to contribute to exhibitions, events and workshops. Knowing that an institution has chosen you to be the recipient of a prize, award, funding or a residency is a great boost to a practitioner’s confidence. Making the most of that includes “after care”; which means publicising and archiving the achievement.

Screen Shot of winner Michael Marriott’s installation for Furniture: Jerwood Applied Arts Prize 1999

Furniture: Jerwood Applied Arts Prize 1999

“Zones of Contradiction”

by Liz Farrelly

pp.8–11

The Jerwood Applied Arts Prize may be the most prestigious and lucrative European award presented to craftspeople, but it is as (in)famous for the consistently contentious decisions of its judges. In 1999 the Jerwood Prize celebrates outstanding recent innovation in furniture: it is not intended to reward a maker with a lifetime’s achievement medal. Innovation is a difficult thing to assess, and sometimes to stomach, especially, it seems, in the crafts world where detractors are vociferous and dedicated. I would suggest, though, that such opposition is a good thing. A well-defined tradition provides an obvious hierarchy against which to kick, a prerequisite of innovation being that it exists on the edge of acceptability.

Welcome to the edge. In relation to other well-defined areas of craft practice, furniture presents us with a problem. It doesn’t cleanly fit the definitions – art, craft, design – as a piece of furniture may be any, or, all of these. Plus, of all the three-dimensional creative media, furniture if the most familiar, the one we interact with every day of our lives – sitting, sleeping, eating, working, relaxing, in the house, garden, park, theatre or restaurant. Whatever we do, wherever, we all use, abuse, ignore, own and enjoy furniture, which is more than can be said for some of the more esoteric disciplines.

Being so integral to our work, rest and play, furniture has no pedestal. Therefore we are more prone to make judgements based on its functional capabilities, and to downplay its potential for intellectual, narrative or contemplative engagement. Furniture may enjoy an advantage over other creative forms in that it is indispensable, but the downside is that it may be considered as an anonymous ‘non-art’.

Before we go any further, let us define just what furniture means in the context of the Jerwood Applied Arts Prize, which is, after all, a competition for craftspeople. In this context, furniture can be a hand-made one-off, commissioned direct from the maker, and it can be a machine-made multiple bought from a high-street retailer. The bottom line for consideration in this competition is that the furniture practitioner shows that they work ideas out through making. But that process does not necessarily apply to the end product which you see in the gallery or on the pages of a mail-order catalogue. Rather, the stipulation is that making is an element of the creative thinking which leads to the final object.

When considering a definition of furniture beyond the Jerwood Applied Arts Prize rules, but in relation to the triptych of art, craft, design, it is obvious that furniture practice operates beyond such one-track-minded considerations as, the kudos-generating mark of the artist, hand-crafted, one-off or designer-label brand equity. So, what is it? I’ll be bold and suggest that furniture practice is an expression of creativity realised in three dimensions, and that the best of it revels in pushing down those sacrosanct barriers between the holy triptych, and then stomping all over tired stereotypes.

What particular qualities do furniture practitioners possess that facilitate such ends? Well they have developed hand-making skills through their educations and careers which enable them to understand and exploit the properties of a wide range of natural and man-made materials – from green wood to carbon fibre. They are invested in concepts of quality which are particular to their genre, but simultaneously, they reassess, redefine and subvert those accepted standards. They also manipulate materials, models and prototypes, in real time and space, and then adopt any number of diverse or subsidiary procedures, whether that be selecting ready-made elements, contracting-out particular tasks to specialised makers, overseeing batch-production within their own studio or with a fabricator, or specifying an appropriate method for mass manufacture. The definition is wide.

That initial process of making decisions by way of manipulating forms and materials, however, is common to all craftspeople. In the realm of furniture, it is often only a starting point, and it is at this moment that the practice of furniture designing/making fans out into a myriad of approaches, methodologies and attitudes. That diversity makes it, in my opinion, well able to meet the requirements of today’s discerning and well-defined niche audiences of consumers and collectors. It may also hold the clue to the future relevance of craft practice. As furniture is all things to all people it gives a vote to diversity over the monolithic canon – in working methods, materials and aesthetics, retail dissemination and mass-media coverage.

Most delightfully, furniture practice incorporates and celebrates contradiction. The whole genre is, as far as I can tell, a mass of postmodern dichotomies made real. It is messy, not hermetically-sealed, tidy or elite, all (unwarranted) salvos which are fired off at the crafts in general.

The four “zones of contradiction”, which, I suggest, define the parameters of contemporary furniture practice, and which therefore, I think, inform the practice of various individuals on the Jerwood Applied Arts Prize shortlist, are, in no particular order; public/private, cheap/precious, familiar/iconic, ecology/technology. I am going to keep the discussion deliberately vague, as this essay is not intended as a textual analysis of specific practitioners and their output. Instead, this is an initiation into inclusive thinking, where opposites are seen to attract and extremes are revealed to be intrinsically linked, the aim being to invite the viewer to play with ideas, and make unapologetically personal judgements. It is a tricky template, because in a world where the media continually attempts to formulate us, what better method for counteracting its propaganda than by rediscovering our own instinctual preferences?

I am defining public/private as the public persona of the designer/maker versus the private, domestic, nature of their work, which of course, becomes public property by being featured in the media. In the furniture world, young practitioners face major career decisions early on, which may brand them for life! The options are: whether to emigrate to Milan (the epicentre of the contemporary furniture industry) and work in the studio of a living legend; be an anonymous in-house fixer for a multi-national retailer; design, produce, market and sell your own product range; create exhibition pieces and wait for commissions; diversify into model-making, interior design and shop-fitting; teach, write, freelance, “assist”, in order to pay the bills. Because of the investment of time, materials and tooling which furniture production requires, on every scale from one-off to mass production, the going is tough. But whereas during the recession of the late-1980s/early-1990s, young furniture designers were either fashionably thin (i.e. starving) or kept their heads down in very unstable jobs, by the late-1990s a key change had occurred.

Today, furniture is the new rock and roll, with the spotlight of media attention creating a bevy of industry stars. You know who you are! With “shelter” magazines such as Wallpaper, Elle Decoration, Living Etc and Space (a supplement of The Guardian); expos such as 100% Design, Spectrum, and (the revamped) Ideal Home Show; and top-rating, interior-design TV shows such as Changing Rooms, encouraging a generation tired of shopping for clothes, clubbing and the rest to lavish funds on their newly purchased nests, everything “home” is top of the style agenda. Some questions remain to be answered. Is furniture the new fashion? Will the issuing of biannual collections encourage profligate patterns of consumption where last year’s cover-shot models will be unceremoniously slung on the scrapheap, and if so, what’s next? And how does all this relate to the age-old values of furniture production, e.g. quality, craftsmanship and longevity? Can furniture practitioners reinvent the genre as well as they are reinventing themselves?

Talking about cheap/precious, I am interested in that giant chasm with divides the stuff you buy flat-packed at IKEA, and the stuff that goes into a gallery (somewhere like the Crafts Council or Contemporary Applied Arts) onto a metaphorical pedestal with a “please do not sit” sign to indicate that “this is not a chair”. Nestling between the two extremes are the temples to design – SCP, The Conran Shop, Atrium, Aram, Coexistence, Purves & Purves, Viaduct, Same (…so many these days). Prices for a chair vary from £20 to £20,000. Ask yourself what it is you’re paying for, aside from the functional aspect of sitting, lying, resting etc., and the cheap/precious dichotomy begins to indicate just how sophisticated a commodity furniture has become. We are, after all, defined by what we own.

But furniture practitioners seem able to defy categorisation because of what they design. Straddling the cheap/precious divide in a schizophrenic kind of way, designing for production, or to commission for a generous collector, or even chucking the restrictions of furniture and producing, gasp, an installation, some of today’s practitioners demonstrate the genre-defying flexibility of a contortionist. And that is a precious ability considering on what a financially insecure, recession/boom-based economy we are building our house of cards.

Aesthetically, the familiar/iconic division offers a catch-all, from the sublime to the ridiculous, if you like. When I say familiar, I mean that which the user feels at ease and happy to interact with. Therefore the vogue for simple, flexible furniture, and witty, salvaged or ready-made assemblages may be considered at the familiar end of the scale. By contrast, the iconic suggests to me, a piece which represents more than it “does”, which stirs memories and emotions, or demonstrates a new way of thinking, doing or making. At the iconic extreme, the object may regally inhabit a space, almost to the point of simulating the presence of a living thing.

Some practitioners are combining familiar and iconic by creating families of products, which interact with each other, their setting and the user, in order to excite specific responses, the aim being to counteract the spectre of alienation by re-humanising our environments. As consumers we feel connected because we share in that family, we get the joke and we speak the same language. This is active socialism/socialisation, with a small “s”.

Also getting in on the act are those brands and labels which have proved so popular with consumers of other products and are now selling us “couture homewares”; cushions, candles, sofas, and beds to complete our life-styling. They happen to be both familiar and iconic too. As consumers we are able to choose between the extremes, or mix and match to create our own combination. Unsurprisingly, furniture practitioners are doing just that too, mixing up cheap and familiar and precious and iconic, or the other way round, as they sail between poles on this continuum of contradictions.

Some might say that the ecology/technology zone denies any continuum of contradictions because they each encompass such fundamentally opposed extremes of attitude and effect. I say they are considerably closer, and closely considered by industry as it strives to clean up its act, and by the ecology movement as it switches gear from niche to mass. The camps are realising that the only way out of our environmental mess is for the two to become inextricably intertwined.

Meanwhile, in the realm of furniture, there is another layer of meaning to investigate. In some quarters ecology may be equated with using wood (green or sustainable), and therefore linked to traditional aesthetic and qualitative values. Conversely there is an opinion that technology pushes furniture into the mould of being designed, manufactured and consumed like industrial design, with the ubiquitous ideology of planned obsolescence added to the mix. Value judgements get bandied about, objects are considered to be honest versus soulless, different materials connote good or evil, for instance wood versus plastic, and the walls go up. I would suggest that such stereotypes are being cleverly and productively subverted, for all our benefits. Plastic may be used, but it may have been recycled once already, or a particular mix is specified because of its low toxicity. Wood may be used, not as a precious value-adding material, but en masse, pumped out from a solar-/wind-powered production line sited deep within a forest.

Whether we choose to use furniture as a working tool, enjoy it as a narrative device, indulge in a label fetish, or support an ideological stance that is beneficial to a wider constituency than just the consumer, the possibilities are endless.