It’s the Summer Solstice and I’m re-posting this article as the Glastonbury Festival kicks off and protesters take to the streets for a Day of Rage. In heatwave temperatures (warmest since 1976), the soixante-huitards’ slogan, ‘les pavés, la plage!’ (translates as, under the paving stones the beach) is ringing in my ears. It’s twenty years since I went to Glastonbury; 1997 was a mud bath, two years before it had been glorious sunshine. Both times friends were made and tested, and despite the odds familiar faces popped out of the crowd. That era was all Parties & Protests and although my plans to visit a Euro Teknival didn’t materialise, later that summer I made it to Burning Man in the Nevada desert and learnt the mantra of hydration from the daily newsletter, Piss Clear!

Much has changed; the underground events mentioned in this article were organised without the aid of social media and minimal Internet coverage, even though I make much of ‘the daily mayhem of mobile phones, faxes and pagers’! One source of information (not mentioned in this article, but I wrote about it another time) was the indomitable SchNEWS, a photocopied newsletter reporting on legal and political campaigns and listing direct actions. It worked like this; you posted them a pile of stamps and they mailed you weekly issues. I met the photographer, Nick Cobbing, through SchNEWS, and by an odd quirk of fate have ended up living next door to their old office!

Now, come the summer there’s a stage in a field catering to every taste and subculture. Festivals are bespoke, niche, glampy affairs, with fancy dress, boutique beers, Insta-Stories and Twitter-Moments. This branch of the music, entertainment and events industries has blossomed, fanned by the British love of a camp-fire sausage and a piss-up in a tent. But I’d suggest that the roots were there back in the 1990s, as innovation and diversity were the order of the day. So I’m not complaining, just suggesting that an updated article would be a whole other story. On a more serious note though, the Millennials have discovered politics, and protest is once again in vogue…plus, we have the weather for it.

‘Anarchy in the UK’

by Liz Farrelly

Blueprint, No.141 July/August 1997, pp.38-40

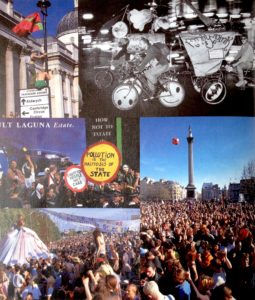

Standfirst: Summer festivals transform our cities and countryside into outlets for pleasure and protest, says Liz Farrelly. Photographs by Nick Cobbing

Music, colour, light, air, trees and grass, bonfires and naked flesh. Festival fare needs rationing. It’s all too decadent, but weather permitting (or add “mud” to the above), come summer we get our fix. I’m still recovering from making 100,000 new friends at Glastonbury, and positively reeling from “the best illegal dance music party in history” (Tony Marcus, Mixmag), hosted by transport activists Reclaim the Streets back in May, which despite heavy-handed police tactics, redefined Trafalgar Square for 20,000 ravers, Liverpool dockers and tourists alike. But I’m also making plans to haul up a marquee at the eco-powered Big Green Gathering in July, and to round off the summer with a “Teknival”, an itinerant illegal rave still allowed to flourish somewhere in Europe.

Excessive? Why yes, and why not, for without these periodic oases of pleasure, summer in the city is one big riot just waiting to happen. According to Mikhail Bakhtin, the Russian theorist of the “carnivalesque”, the harvest festival was a safety valve, an antidote to respectable, responsible (law and) order, when “the world turned upside down”. Landowner and peasant swapped roles and misbehaved, but only for a night. Under the sanctioning label of “tradition”, this controlled explosion guaranteed another year of the social status quo.

The underlying principle of the carnivalesque was the opposition between the classical and the grotesque, the harmonious and the shifting, the controlled and the teeming. This lives on in the summer festival, carnival and demo season. Leaving the pressure of modern life behind, today’s “upside-down worlds” have become an antidote to the daily mayhem of mobile phones, faxes and pagers. The party is often saner than the morning after. The major difference between Bakhtin’s Russia and our postmodern isle is choice. You pay your money, jump the fence, or ferret out the free events, and choose your stance, on entertainment, noise levels, politics and codes of behaviour.

For some the music never stops, and the rave/festival has become a way of life. Matthew Collin, in his book Altered State, traces the rise of Ecstasy culture and notes how the numbers of Thatcher’s children defecting to this permanent impermanence back in the mid-Eighties “struck fear into sections of the government that believed the travellers’ way of life involved a rejection of the system of property and land rights on which Britain is based”. You may prefer your semi to a Sherpa van, but that defiant spirit of freedom infects even the most urban of festival contexts, where you share space with a range of impermanent communities, whether they’re on stage singing, or selling brandy coffees brewed on a stove in the back of their “rig”.

George McKay, in Senseless Acts of Beauty, a scholarly history of such things, describes the characteristics of what American theorist Hakim Bey calls a “Temporary Autonomous Zone” (TAZ); “pirate economies, living high off the surplus of social overproduction… and the concept of music as revolutionary social change… (an) air of impermanence, of being ready to move on, shape-shift, re-locate to other planes of reality… a guerrilla operation which liberates an area of land, of time, of imagination and then dissolves itself”. McKay also states that “to be effective fairs must refer outside themselves, not exist solely as insular, narcissistic concerns”. He traces direct lines of influence, via active participants, from the post-war revitalisation of traditional horse fairs, to the occupation of Stonehenge in the early Seventies, and to Glastonbury and rival commercial rock events. This lineage of alternative events and resistance cultures was re-politicised thanks to the Criminal Justice Act, when protests united ravers, activists, travellers and anyone who cherished their basic civil rights to march in protest.

That recent drive to protest culminated in a monumental rave on Castlemorton Common in deepest Worcestershire, the success of which spurred Michael Howard [then the Conservative government’s Home Secretary] on to formulate his repressive legislation. In May 1992, 50,000 young people from all walks of life gathered for eight days and nights of techno music, circus entertainment and al fresco living. Not one flyer was printed. News spread via word of mouth and national television coverage of irate villagers. The result, as Michael Collin remembers was “a fully functioning independent state under the sole control of its inhabitants… a twenty-four hour city”.

When people party in protest they create a “walking fun city”, from a combination of state of the art audio technology (Technics turntables, Gemini mixers, JBL speakers), heavy goods vehicles and hatchbacks, tents, caravans, stalls, canvas, washing lines, trestle tables, bin bags, and salvaged pallets, oil drums, bread crates, whatever…

Castlemorton was an extreme example of this, but McKay and Bey’s TAZ functions just as happily in the environs of Edinburgh as it does in Glastonbury, where a temporary city appears on a convergence of ley lines. The sight is awesome. Sitting high in the “sacred space” by the “new” stone circle, topped with drummers and dancers an 800-acre [corrected from subbing mistake] rural city sprawls across the misty Somerset valley. Scale is defined by the huge, but dwarfed, wind turbine which powers the main stage, and the flashing light of emergency vehicles which constantly crawl through the site.

The division of Glastonbury into two distinct areas, Avalon and Babylon, means you can tailor your experience of the event. Stick to the Green Field area, with its healing circles where trees sing (no joke), where you can enjoy a massage in a bender (a geodesic dome constructed from saplings and tarpaulin), or learn to carve wood, and you can ignore the main drag with its resemblance to Oxford Street on Christmas Eve, and music biz hierarchies. Alternatively, you can mosh around in the font-of-stage pit.

Similarities abound with Edinburgh, where for the last fortnight of August every year, a permanent city simply dissolves. The Athens of the north becomes a showground. Buildings are obliterated with banners and bunting, the streets are paved with discarded flyers, no one sleeps, clowns roam Princes Street and everyone’s a performer, talking too loud and drinking too much.

When Reclaim the Streets held a party last July on a stretch of motorway in central London [watch the film about 13/7/96, here], that Temporary Autonomous Zone invaded an off-limits area. They chose a spot where no one’s ever even walked their dog, and made the point of digging up the M41. Shielded from the prying eyes of the Metropolitan Police, underneath the stilt-walker’s Marie Antoinette skirt, the diggers planted saplings. Meanwhile children played on a trompe l’oeil beach and fancy-dressed ravers danced with locals, who despite the beats per minute, declared that they’d never heard the road so peaceful.

Challenging the status quo, redefining a landscape, freeing captive space, taking to the streets, living in a tent. From letting your hair down to opposing imposed value systems, festivals, demos and parties provide an opportunity to digress and transgress. As you drive along the M41 you may still see the signs, the flowers painted on the tarmac. The message of protest is clear, whether you heard it in a field, in Finsbury Park, or on the hard shoulder.

Photographs are by Nick Cobbing, apart from Bristol (by Will King Skyrock Photographic). The montages were by Blueprint’s Art Director, Andrew Johnson.

Original captions: [first montage] Campaigns and protests are the traditional impetus for festivals (top left and right, demonstrations of solar and wind power at the Big Green Gathering). Music sets the tone of a festival (centre left, preparing sound gear) and provides the catalyst for summer revels (centre right, an Exodus party in an abandoned quarry near Luton). Occasionally the considered use of form and materials in a festival structure indicates the work of an architect (bottom left and right, the reusable information and merchandising pavilion designed and constructed by Alastair Green of Ground Zero Architecture and Jonathan Mosley for Bristol Community Festival). [second montage] Urban festivals take the form of carefully organised and controlled entertainments, like the annual event in Edinburgh, or can be anarchic and deviant, like the Reclaim the Streets protests in London (all images). Either way, buildings are often subverted by decoration, hoardings, graffiti or blatant attack and the usual motions of the city are threatened.