National Museum of Ireland

Archeology

Kildare Street, Dublin

Permanent Collections

Visited 25 May 2013

Even though I’ve been to Dublin many times, this was my first visit to one of the city’s three sites that house the National Museum of Ireland. Having read about the museum’s development in Anthony Burton’s Vision & Accident: The Story of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A Publications, 1999), I was interested to see if its 19th-century roots, administered by the Department of Science and Art, as part of its “South Kensington system”, might still be evident.

Today the museum combines a distinctive building and interior, a world-class collection, and a friendly, inclusive “interface”. Founded in 1877 as the Museum of Science and Art, it brought together a number of collections and institutions (not unlike the Victoria and Albert Museum’s origins). The museum building in Kildare Street (and its opposite twin, the National Library of Ireland), resulted from an architectural competition won by Thomas Newenham Deane, with the purpose-built museum opening in the 1880s. The two institutions flank the 18th-century Leinster House, originally home to the Royal Dublin Society, it became the new nation’s parliament building on independence from Britain in 1921. The proximity of museum to government points to the importance the Nationalists afforded to the exploration and preservation of Ireland’s cultural heritage.

Both the museum and library are beautifully decorated, displaying examples of Irish, British and European craftsmanship and manufactures (carved wooden doors, mosaic floors, staircases of deep-green, Irish marble). A member of staff mentioned that much of the original fabric of the museum had been painted or boarded over, with tiled floors hidden and vibrant ceramic decoration white-washed (in an attempt to provide a neutral backdrop to exhibits, as happened at the V&A in the 1950s), but that a renovation programme has uncovered and restored these (generally well-preserved) decorative elements.

From the website: “Particularly lavish are the majolica fireplaces and door surrounds manufactured by Burmantofts Pottery of Leeds, England, and the richly carved wooden doors by William Milligan of Dublin and Carlo Cambi of Siena, Italy.”

Next time I’ll visit the Decorative Arts and History galleries at Collins Barracks (opened in 1997 and home to artefacts from the Museum of Irish Industry, some of which were purchased from the Great Exhibition in 1851, and many of which had been in storage since 1922). But on this particular sunny Saturday, I chose to explore the Archaeology collections, which begin in the Mesolithic Age and continue until Medieval Times, concentrating on Irish objects, ancient objects collected by Irish historians and archaeologists, and objects evidencing trade and contact with other countries and civilisations.

The museum was just the right amount of busy, and FREE! There’s plenty to see, read and watch, enough for an entire day of wandering and wondering. Plus, the cafe looked amazing, but we took our snack break across the courtyard in the National Library, in a dining room that provided a quiet oasis of calm in this frantic tourist town. Also on view in the library was an amazingly atmospheric temporary exhibition “Yeats: The Life and Work of William Butler Yeats”, combining immersive room-sets, multiple-media (audio and visual recordings and protections), historic artefacts and archival documents.

Start your visit to the museum by passing through the rotunda entrance (and gift shop) with its magnificent mosaic floor of astrological symbols, leading into the main gallery, with glass and cast iron roof and balconies above. The ground floor houses Europe’s largest collection of prehistoric gold artefacts (from 2200BC-500BC), including the jaw-dropping Glenissheen Gold Gorget (800-700BC). The “hoards” (technical term) are completely mesmerising, displayed in well-lit, minimalist cases, arranged around various “pavilions”, providing contextual information and images, which manage not to distract from the magical objects. Not all are gleaming gold though. Also on show are Bronze Age and Iron Age ceramic and wooden artefacts, a stunning ancient wheel on tracks and some objects, such as this wooden bowl, which are so perfectly preserved thanks to the unique qualities of the peat bogs they were buried in (the actual chemistry/biology bit is well-explained).

In fact so mesmerising is this gallery (there’s a massive dug-out canoe too), that I exited on the far side (missing the designated route), straight into a gallery dealing with Kingship and Sacrifice, which contains the human remains of victims of either sacrificial killings or territorial skirmishes. I’m not very brave when it comes to viewing human remains; dry bones I’m just about OK with (plenty of those upstairs in the Viking Dublin gallery), but add skin and hair and I’m not happy at all. My companion opted to see the (partial) bodies and was awestruck. Housed in beautifully constructed, white-walled roundels, photographs and text at the entrances prepare you for the sight, but you may choose not to enter. As the actual remains are protected from the easily shocked, the resulting calm (no squeals) adds to the respectful, somber atmosphere. I felt that the substantial constructions, which took visual cues from simple tombs, proved to be suitable resting places for these Irish ancestors. This replica of the giant, silver Gundestrup Cauldron (found in a Danish bog), resplendent with images of Celtic deities, provided further clues as to the sort of sacrificial rituals that may have led to these individuals’ demise.

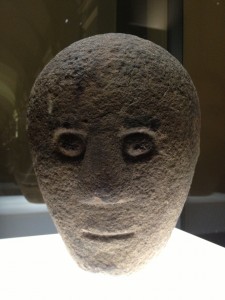

Some of the most iconic and precious objects from the collection are housed in The Treasury, a series of galleries chronicling the development of Irish art/artefacts from the Iron Age to the 12th century, incorporating the adoption of Christianity and the influence of Celtic and Viking forms and motifs into ritual, decorative and functional objects. For me, the most enigmatic is the three-faced Stone Head, aka, the Corleck Head (1st to 2nd-century AD), found in County Cavan in 1855, perhaps because it bears an uncanny resemblance to my Dad (a Cavan Man himself).

Beautifully imagined and skilfully crafted objects, such as the gold Broighter Boat along with its tiny Cauldron (from 100BC), and the “Tara” Brooch, a silver-gilt annular brooch from the 8th-century AD (an example of the Celtic-influenced La Tène decoration), represent high points in the development of skill and technique that stretched across a millennia.

All in all, the museum is a magical place, full of stunning objects telling fascinating stories about the development of a civilisation that was complex, diverse and not without its share of conflicts. More information can be found on the museum’s slightly perplexing website and via the multiple-media “100 Objects” project, here and here. Also, look out for this BBC documentary, Irish Treasures Uncovered presented by Dr. Alice Roberts, which focuses on a number of objects from the National Museum of Ireland and discusses the legal wrangles around repatriating objects, from both Belfast and London, post independence.