As a tie-in with Bloomsbury Academic, publishers of Design Objects and the Museum (see, here), Joanna Weddell and myself were invited to give a Lunchtime Lecture at the Victoria and Albert Museum. As we shared the time-slot our talks were short and aimed at a general audience, but both are based on doctoral research, and the blurb draws connections between our projects, so I’ve included it in full before posting an edited version of my talk with the slides, which provided an additional strand of information supplementing the visuals.

Contemporary Design Objects in the Museum: Two Perspectives

The Lydia and Manfred Gorvy Lecture Theatre

Victoria and Albert Museum

Cromwell Road, London SW7

26 April 2017

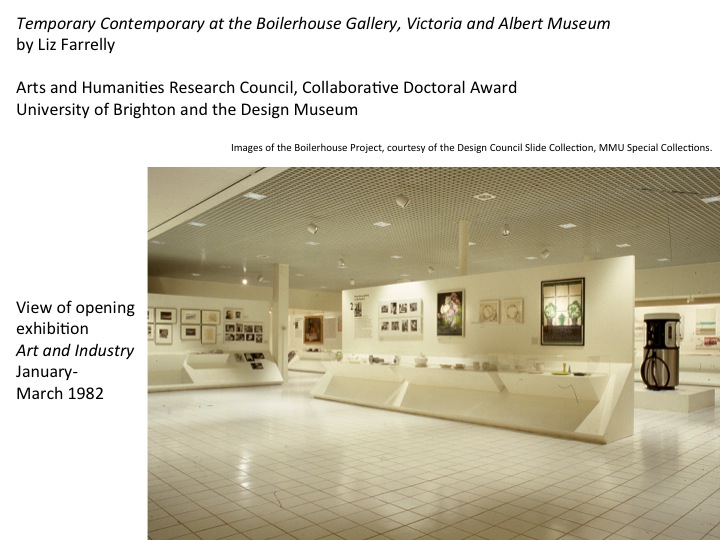

‘This lecture will examine the exhibition of 20th century design. Circulation, or ‘Circ’ was responsible for many of the Museum’s acquisitions of post-war contemporary design. Joanna Weddell will discuss Circ’s role as a ‘museum within a museum’ through shows such as Design Review, 1975. The Boilerhouse Gallery was a temporary intervention at the Museum funded and run by the Conran Foundation, as Liz Farrelly will explain. Betweeen 1981 and 1986 the Gallery increased the visibility of contemporary design through thematic exhibitions that booted visitor figures and grabbed headlines, later morphing into the Design Museum at Shad Thames.’ Lunchtime Lectures Summer 2017, V&A.

As a writer and academic, I’m interested in how contemporary design is collected and displayed in permanent and temporary exhibitions, and how the museum as an institution creates meaning. I’m writing a doctoral thesis about design museums, but instead of producing a history of my case study, London’s Design Museum, I’m looking at moments when change occurs within the institution.

I’m considering the institution as a designed object, looking at the production, consumption and mediation of the Museum’s cultural production, in the form of its programming, exhibitions, displays, catalogues, marketing, and environments. I’ve been observing the institution’s working methods and how different people interact with the Museum, and have interviewed key personnel past and present.

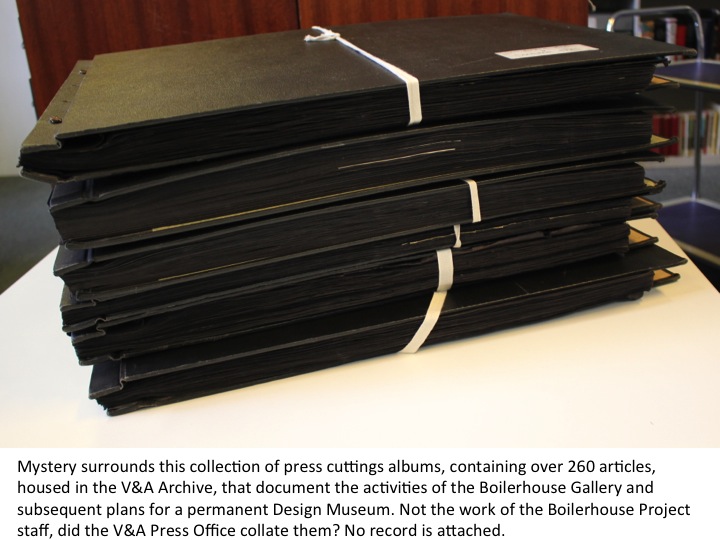

I’ve also reviewed media and literature relating to the Museum, including the contents of these press cuttings albums, housed at the V&A’s Blythe House Archives. My mix-and-match methodology borrows from Discourse Analysis, Qualitative Research and Actor Network Theory, with the aim of triangulating this historical and empirical material so that rather than validate any one version of events, my research will provide material for discussion, crossing over between Museum Studies and Design History.

We’ve just seen an ‘updated’ version of the Design Museum open in the former Commonwealth Institute on Kensington High Street; before that, over quarter of century, the Design Museum at Shad Thames had developed into a popular London landmark. But its first incarnation may be less familiar; between 1981 and 1986 it existed as the Boilerhouse Project, with its public-facing Boilerhouse Gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum on the site that is now the new Exhibition Road Building.

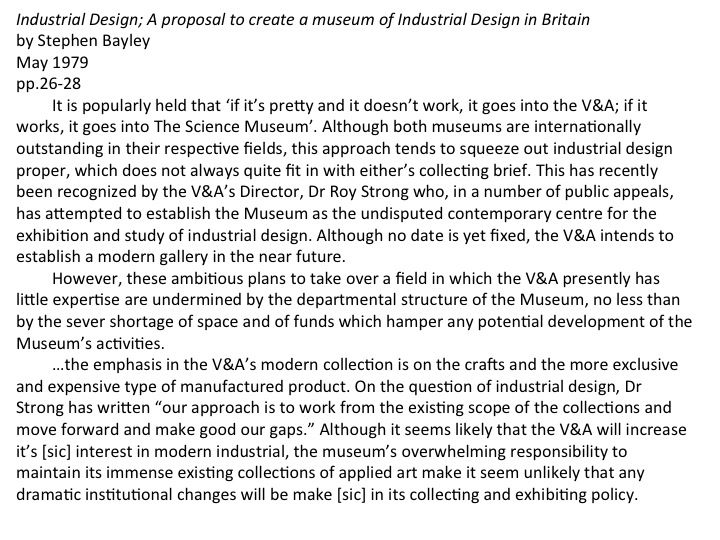

Bar some earlier conversations, this initiative began when Terence Conran commissioned Stephen Bayley to write a proposal for a new museum, which he completed in May 1979. The aim was to open a ‘Museum of Industrial Design in Britain’ under the umbrella of an educational charity, the Conran Foundation, to be funded by the stock market flotation of Conran’s homewares company, Habitat. I found a copy of this report in the papers of a former Director of the Design Council, Sir Paul Reilly, held in the Archive of Art and Design. Reilly had introduced Bayley to Conran and will become Chairman of the Trustees of the Conran Foundation. In the report, Bayley lists museums around the world that he identifies as dealing with design, including the V&A.

Bayley cites the separation of the arts and sciences as cause for why Industrial Design, and by implication contemporary mass-produced objects are a difficult fit for traditional applied arts museums. He is aware that the Director of the V&A, Roy Strong, plans to open a ‘modern gallery’ but questions whether the V&A possesses the right ‘attitude’ or ‘expertise’ to achieve more than ‘superficial’ results. The implication is that the Conran Foundation could provide the much needed ‘space and funds’, unencumbered by an ‘immense’ collection or the time-consuming requirement of updating a museum-wide collecting policy.

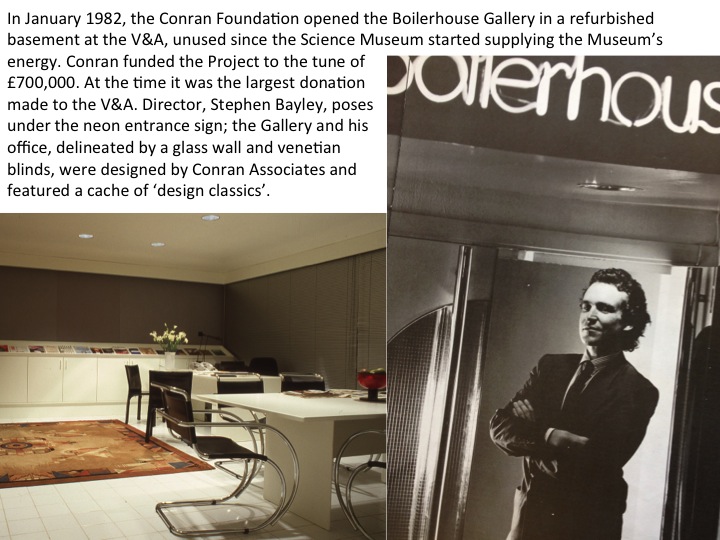

Sir Roy Strong invited the Conran Foundation into the V&A to set up the Boilerhouse Gallery, which opened its first exhibition in January 1982. Financed by Conran and designed by Conran Associates, a refurbished basement was transformed into a white, gridded box, at the cost of £700,000, which was the largest donation to the V&A to date. A five-year ‘licence’, in effect a lease, was signed but only after Strong interceded with the Treasury, which wanted ‘to veto it on the grounds that outside interests should not be housed on Government premises’, as he explained in The Roy Strong Diaries 1967-1987 (1997). He also recalled that, in order to authorise the Project the Treasury classified it as a temporary exhibition.

The Boilerhouse Project was not a museum department, instead it remained an independent entity, and therefore, ultimately beyond the control of Strong. This liminal status caused administrative confusion within the Museum, which itself was undergoing the torturous process of transitioning from government control into a Trustee Museum. With power structures within the institution experiencing unprecedented upheaval, the introduction of such a high-profile interloper caused additional friction and became the focus of wide-ranging frustrations. Anecdotes about the resulting culture clash can be backed up with archival evidence in the form of correspondence, often enlivened with multiple annotations tracing the bureaucratic route of memos between the Directorate, Curatorial Departments, Museum Administrators and Civil Servants.

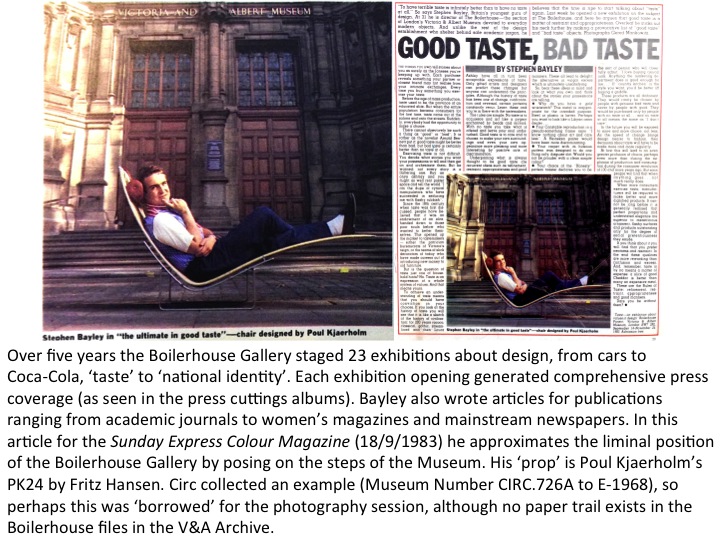

Front and centre, and often instigating these conversations, was Stephen Bayley, the 29-year-old founding Director of the Boilerhouse Project and subsequently the first Director of the Design Museum. Previously, he had been a university lecturer teaching Art History and, concurrently, a journalist writing about art, design and culture notably in the Design Council’s Design magazine. Both in print and when interviewed, Bayley admits to provoking the V&A’s ‘old guard’ of Keepers (the Museum’s arcane title for curators) and Administrators by questioning or ignoring institutional procedure, including the dictates of the Official Secrets Act, which Museum staff were required to sign, and dressing ‘like a banker’ (his words). As a ‘designed’ object himself, Bayley set out to ‘fashion’ a new type of curator, a design curator, by using his appearance to reference the 1980s business milieu and the commercial success of the design profession, which, thanks in part to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s de-regulation of London’s financial sector, was booming, creating the so-called ‘designer decade’.

Bayley instigated a fast-paced culture of change at the Boilerhouse Gallery, staging 23 exhibitions (most with an accompanying catalogue) and hosting high-powered events and well-attended openings that generated a substantial amount of press coverage. As there was no advertising budget for the Gallery, these articles in mainstream and trade publications provided ‘free publicity’ for the Project. Subsequently, this coverage prompted debate about contemporary design, its role as an economic stimulus and its status as cultural expression. Along with impressive visitor numbers (which were often quoted by Bayley as evidence that the Boilerhouse Gallery was more popular then the rest of the V&A), these indicators were seen as proof of concept, of an eager audience for design exhibitions. In turn, these proofs were used to sell the idea of a new Design Museum to prospective sponsors.

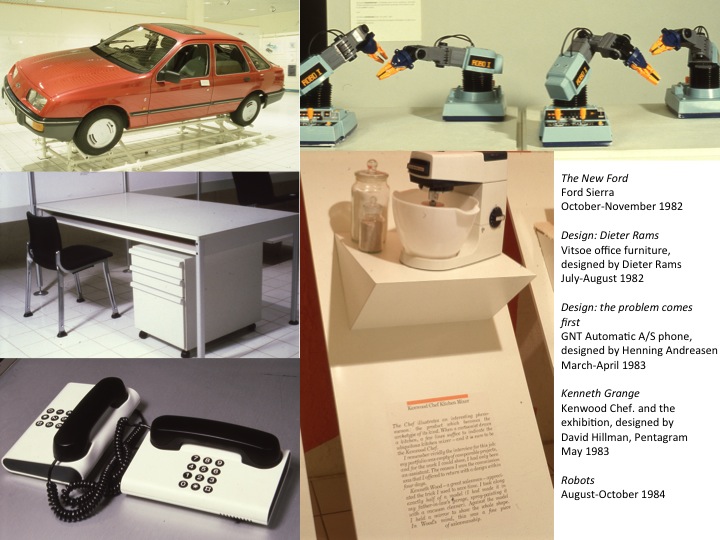

The range of exhibitions stage in the Boilerhouse Gallery was diverse and unprecedented for the V&A. Some exhibitions were generated in-house, others were drawn from an international network of institutions and curators cultivated by Bayley since his research trip for the initial report. In an article by Beryl McAlhone, in Campaign magazine (1/2/85), Bayley described his curatorial approach as ‘Three-Dimensional Journalism’, in that it offered ‘something new to think about every few months’, the aim being to attract repeat visitors and build an audience for design. This way of working, to tight deadlines, juggling content, was another source of friction between the Boilerhouse Project and the V&A’s Directorate and the Administration; repeated requests for Bayley to produce long-term planning documents, beyond a bare-bones ‘list’, were ignored.

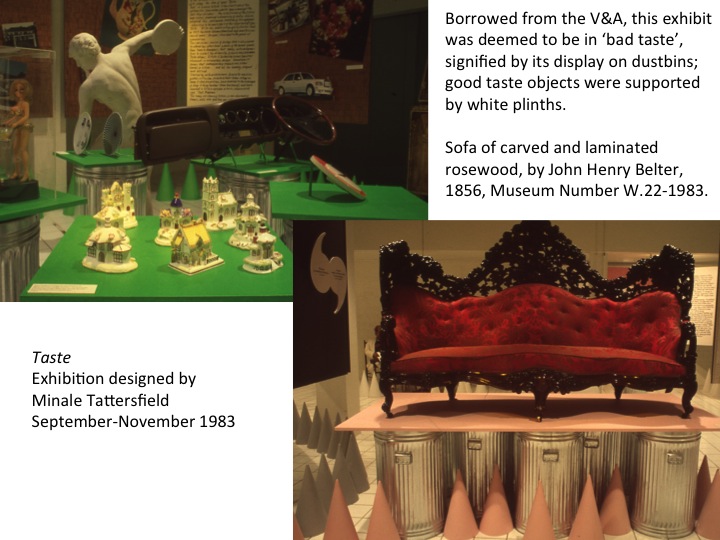

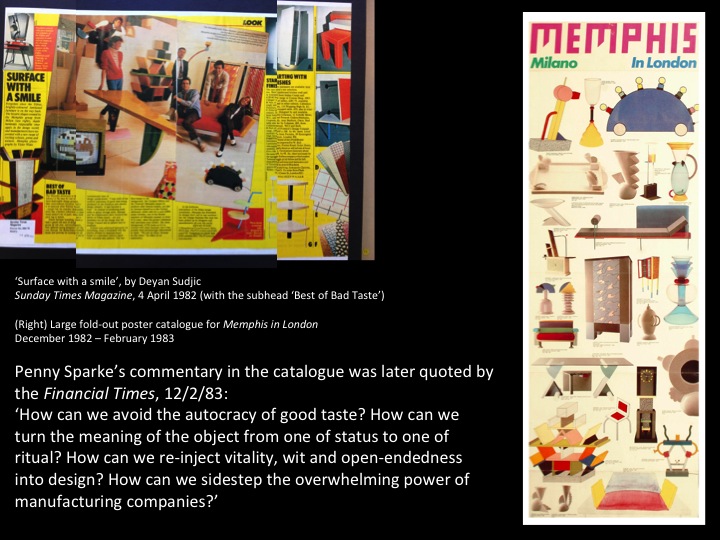

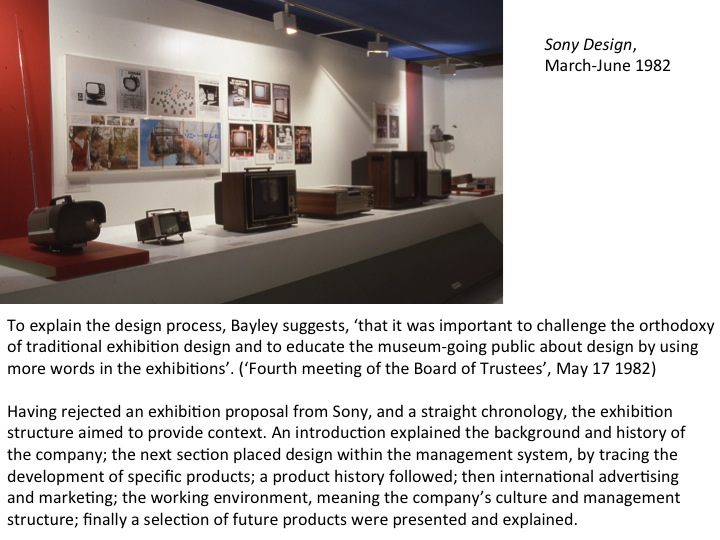

In her article, McAlhone points out that the more ‘serious’ exhibitions staged in the early years of the Boilerhouse Gallery such as, Art and Industry, Sony Design and Dieter Rams, were supplanted by sensational, provocative and playful shows, such as Memphis, Taste and Post-Modern Colour.

In reply Bayley explained: “‘It’s a populist position…you can’t do narrow intense displays solely for professionals…you do get hooked on the public after a while…We’ve realized more and more that exhibitions in the Boilerhouse are just three-dimensional journalism‘.”

That said, his ‘three-dimensional journalism’ could be described as ranging from long-form to sound-bite. The exhibitions were often reactive, sparked by a newspaper article, the cultivation of a contact, or a visit to Milan; for example, the Memphis exhibition suddenly showed up on a list of future exhibitions, not long before it opened. Rather than grounded in the kind of scholarship purveyed by Museum Keepers, the tone of voice of Boilerhouse Gallery exhibitions varied; from Penny Sparke’s theoretical musings about what we might now call ‘critical design’ in the concertina-catalogue for Memphis; to journalist and curator, Jonathan Glancey’s boys-own celebration of trains, planes, automobiles and Swedish ‘blonds’, in the ‘tabloid’ newsprint catalogue, for National Characteristics of Design.

Design solutions for catalogues and exhibition installations aimed to entertain as well as educate and were ‘design objects’ in themselves; some were cheap and cheerful, others dramatic and immersive, with John Weallean’s pop-inspired design for Glancey’s show perhaps the most impressive. A cut-and-paste interactive maze of stylistic forms was used to enliven the blown-up photographs of larger (absent) objects; even when exhibitions contained more images or words than objects an extra layer of design was employed to engage the audience.

The Boilerhouse team acknowledged that their programming constituted uncharted territory; comments in Conran Foundation minutes recognised problems specific to exhibiting contemporary design objects produced by globalised industries. Where institutional design promotion, in the form of the Design Council in the UK, championed British design over imports, the Boilerhouse has to adopte an international standpoint, reflecting the changing nature of global trade. The team also listened to their critics, with Conran himself suggesting (at a Trustees’ Meeting) that ‘future planning must take into account an analysis of negative press coverage’. For example, a critical comment about the lack of British design consultants in the first exhibition, Art and Industry, prompted an invitation to Pentagram’s Kenneth Grange to stage a solo show.

The Boilerhouse team attempted to circumvent criticism of their plans for the Sony Design exhibition, which questioned, why promote a non-British manufacturer? The Board of Trustees discussed the need to avoid an ‘uncritical’, celebratory tone that would reduce the exercise to little more than a trade show or free advertising. To that end, even though the material for the exhibition (objects and images) was supplied by the manufacturer, the Boilerhouse team rewrote the exhibition script and produced and published their own catalogue; therefore all the interpretation came from the Boilerhouse.

Board of Trustees minutes record Bayley suggesting, ‘that the Boilerhouse Project would always face the accusation of being commercial, because it was dealing with contemporary, mass-produced consumer products’. He was asked to ‘draw up a statement of aims and guidelines for how to deal with companies’. Such a document is not included in the Boilerhouse files, but similar discussions are still had within design museums today; London’s Design Museum includes such guidelines in its exhibitions and acquisitions policy.

While the Boilerhouse Gallery was developing this new kind of design exhibition, the culture clash with the V&A continued. Memos requesting forward planning and exhibition schedules were ignored, and exhibition designers complained about the late supply of concepts scripts, exhibits and schedules. Time and again the exhibitions were criticised, both within the Museum and in the Press, for bringing inappropriate objects into the Museum, from cars to Coke bottles, and more than one exhibition prompted a so called ‘scandal’; for instance when the roof had to be removed to crane a car into the Gallery, or when the Sculpture Department took over a gallery en-route and blocked the delivery of Boilerhouse exhibits. And when exhibits from the Memphis exhibition were relocated to Liberty’s Regent Street department store for a selling show, the Boilerhouse Project was accused of bringing the Museum into disrepute with such a blatant rejection of disinterested scholarship. In the end, the practical demands of fast-paced ‘Three-dimensional Journalism’ and the lack of guidelines for dealing with contemporary objects, including the promotion of non-British design, did not fit the culture of the host organisation.

The information and quotes used here are from documents held in the Archive of Art and Design and the V&A Archive; by sifting through archived letters and memos between Museum staff and the Conran Foundation, the causes and effects of institutional friction can be traced and suggested; the primary outcome being the ejection of the Conran Foundation when the initial lease ended in August 1986. Forced to leave the V&A before plans for a new permanent home were finalised, the momentum that generated a new audience for design was dissipated.

The former Boilerhouse Gallery became a space for staging temporary exhibitions of twentieth-century art and design. Strong also introduced the requirement that 50% of acquisitions across all Curatorial Departments be twentieth-century objects (V&A Museum Report of the Board of Trustees 1st April 1986-31st March 1989, edited by Jonathan Voak). This didn’t necessarily guarantee spending on contemporary design as curators could opt to strengthen holdings of Art Deco and Mid-Century design. The perceived animosity between the V&A and the Design Museum may have been fuelled by a clash of personalities and the practical chaos that ensued from a hastily arranged partnership, but it was re-echoed in differing attitudes to a core component of the Boilerhouse Gallery programme, the exhibition of contemporary design.

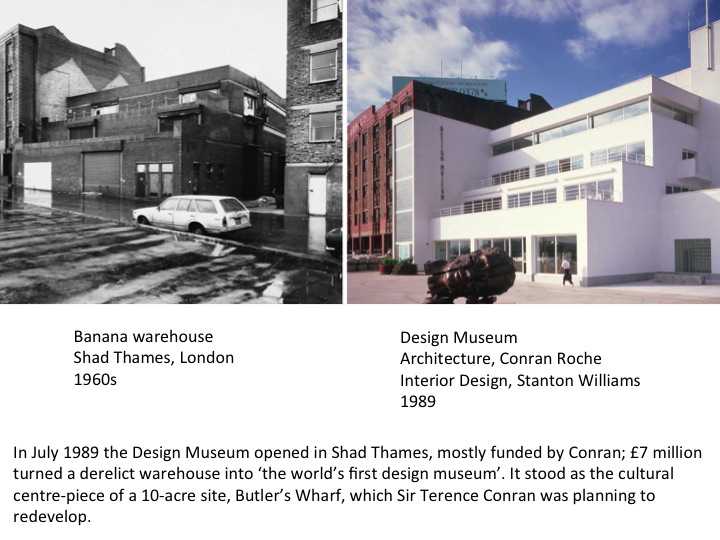

Meanwhile, far from South Kensington, three years working from offices in Conran’s Butler’s Wharf development, the refurbished warehouse in London’s docklands, costing £7 million opened as ‘the world’s first design museum’ (a claim made in its promotional literature). Now that the Design Museum has moved back west, closer links between the two Museums must be on the agenda.

Thanks to Jeremy Parrett at Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections for the images of Boilerhouse exhibitions, from the Design Council Slide Collection.