Teamwork and Strategy in the Museum… Lewis Chessmen, Scotland, 12th-Century, British Museum. Photograph by Andrew Dunn. Sourced from WikiCommons/Creative Commons.

What does data have to do with me?

British Museum

Great Russell Street, London WC1

5 June 2015

One of the bonuses of working on an AHRC funded doctorate is being able to attend conferences, workshops and seminars that introduce me to subject areas which at first sight might seem tangential to my core subject, but as my research actually crosses disciplinary boundaries I shouldn’t be too surprised when they prove to be incredibly useful. Signing up to the AHRC mailing list and taking notice of emails sent by University of Brighton Doctoral College alerted me to such opportunities. Events that fit this category include a two-day workshop, hosted by Northumbria University Newcastle and Tyne & Wear Archives and Museums, on the subject of “Digital Histories: Advanced Skills for Historians” (reviewed here), and “Using Museum Archives” supported by the Museums and Galleries History Group and the British Museum Collaborative Research Studentship Programme (also, to be reviewed).

I was particularly impressed with another British Museum event, “What does data have to do with me?” and am writing this up in detail because it signposted numerous projects that I wouldn’t otherwise have been aware of. The packed programme featured stellar speakers including representatives from Adobe, the Arts Council, Culture24, Dallas Museum of Art (by Skype), Google, The Guardian, Nesta and News UK. Crucially, though, the day introduced a new resource within the museum…data.

Chris Michaels, Head of Digital and Publishing at the British Museum, kicked off the proceedings by telling us that the cultural sector is going through the sort of data processing revolution that totally transformed both retail and publishing. Think of stock control without barcodes or discount coupons without loyalty schemes and that’s where we are now with the use of data in museums. Chris reiterated that museums aren’t just sniffing around digital content (often with delivery-means inspired by the games industry), but are also interested in the “data underneath the content, which helps us understand how it works and can work better”. He admitted that the sector knows little about its audience; in the case of the BM’s 7 million annual visitors that’s a lot of “don’t knows”.

Ironically, museums know more about the visitors on their websites than they do about those in the building. And of course the incentive to fill that info-gap comes from calls for impact studies that evidence engagement and outreach, from funders and government. Another incentive is that “the public wants open content and data”. Demonstrating the British Museum’s commitment to change, Chris cited its new mission statement, “Where the whole world can come and experience the whole world”, and the introduction earlier in the year of a “Digital Strategy and Information Management Strategies”. Quoted in a recent job advert for a Chief Enterprise Architect/Head of Change within the Information Services department, these strategies are intended to “drive and enable change”. However, search the Museum’s website for this “digital plan” and you’ll draw a blank. By way of comparison, Tate’s Head of Digital Transformation, John Stack, blogged about “Tate Digital Strategy 2013–15” with the subhead, “Digital as a Dimension of Everything”, in Tate Papers no.19, Spring 2013, which is accessible on Tate’s Research webpage, here.

In the first batch of talks hailed as “Stories from the data front line”, Layla Barron, Head of Operations at Bristol’s Watershed, demonstrated how audience-focused institutions, i.e. performance venues, are better able to glean information because of sophisticated ticketing systems and, therefore, lead the culture sector when it comes to data collection. (As it was pointed out later in the day, the majority of museum ticket sales are “walk-up” and there’s free entry too, which means “less data”.) Watershed signed up to Culture24’s “Let’s Get Real” initiative, which aims “to define and measure the success online” of UK cultural organisations. [Just missed that conference!] Priority was to make data consistent across the organisation so that statistics would be easy to access. To achieve this Watershed embedding a digital strategy into the business plan, set up a group of “external critical friends” to help evaluate working groups, and introduced new pricing to encourage the under-24s audience, as they were the group with least data. One of the best “take homes” from the day came from Layla’s list of what Watershed learnt from the experience: create teams across departments and staff grades, don’t work in “silos”; language has to be standardised across systems and departments; stage internal knowledge sharing events and encourage peer to peer learning; identify “data champions” and develop their skills; encourage the mastery of EXCEL, it’s a powerful analytical tool; milestones have to be flexible; audits are key; staff training is too; and, as it helps understand customer behaviour, they launched a loyalty card (learning from retail). Layla also advocated using an online tool, the Arts Council’s Audience Finder website that proclaims, “Find out who your audiences are and discover who they could be”. Finally, Layla stressed that no one person could be tasked with making change happen, all staff had to be on board. The process of developing such a “best practice” has taken five years.

Next up, Juan Mateos-Garcia, Economics Research Fellow, Creative and Digital Economy at Nesta’s Policy and Research Unit, asked, “what are we going to do about this explosion of data?” He suggested that we use social media, before and after innovation events like this one, to assess its effectiveness. But, “what skills do we need in order to do this?” Juan suggested that expecting to find the combined skills in one person – coder, statistician, economist and software developer – is like believing in unicorns; these are truly “mythical creatures”. He advocated, “Don’t chase unicorns”, but build diverse teams and stick to free, open access software.

After all the talk of big data, Jon Pratty of Arts Council England’s Creative Media team, suggested making sense of small data by listening to anecdotes, to what he called “frictionless sharing”. For example: “Whose job is it to check that the museum map is correct on Google?” It’s the institution’s job, not Google’s. Extrapolating, he wanted institutions to be data-centric rather than obsessed with digital delivery or new technology; instead understand how “the offer” fits the institution and its USP (unique selling proposition). Research is key as the best experts on any museum (especially small ones) are the staff. Again, Jon gave a shout out to Culture24, for performing a “new cultural role” (launching the “24-hour museum”). He talked about “new roles” for more cultural institutions and that they are “new places for income generation” too. His last buzz-phrase, “relational connectivity”, put me in mind of a new kind of cultural capital (invoking Pierre Bourdieu).

Chair of the first panel discussion, Anra Kennedy, Content and Partnerships Director at Culture24, mentioned one of its long-term projects, “Connecting Collections”…“a new digital service enabling children, young people and teachers to discover and use digital collections content in interactive, exciting ways”. Building community and networks is central to Culture24, and this year’s conference emphasised the convergence of digital technology and museum-based learning. Connecting the arts and technology prompted questions from the audience; issues ranged from “gaining consensus” i.e. definitions – objects, visitors, members (the solution; have meetings, share information); terminology is a problem (yes; linguistic terms need standardising); who should take responsibility for data infrastructure in the Arts? (the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council, now disbanded, was evoked); when is the job done? (answer never; data is constantly developing and policy documents should reflect that). It was suggested that owning and managing data on an institutional scale can be “very, very profitable”. A statement: “We have all the information about audiences we need, but we have to join it up and ask ourselves why we want it”, segued into another comment about the need to link arts and culture with education especially universities, and to learn from retail and transport infrastructure. One suggestion was for Research Councils to stage crossover projects, teaming arts and science institutions. Finally, the UK’s growing “creative industries” were mentioned, the imperative being “to put the academic, cultural and creative sectors together”.

The second session, “Use it or lose it: insights and analytics”, invited media and tech companies on stage and was less about case studies than success stories. Chris Austin, Head of Insights and Analytics at The Guardian, demonstrated design thinking when he insisted, “iterate, iterate, iterate”, as the way to improve the performance of webpages. Underlining that the job is never done, he suggested that data/digital projects start small, keep innovating, are constantly tested; and he opened his toolbox to reveal that The Guardian uses Adobe Analytics, Ophan Dashboard and Tableau to make the most of the data it collects from digital users, both readers and staff. Data is of course crucial to its business, as underscored by its ABC ratings.

The Guardian.” width=”584″ height=”359″ class=”size-large wp-image-997″ /> Screen Shot from a PDF showing a month of online data for The Guardian.

The Guardian.” width=”584″ height=”359″ class=”size-large wp-image-997″ /> Screen Shot from a PDF showing a month of online data for The Guardian.Jamie Brighton of Adobe brought the slickness of a US-style sales presentation to the proceedings, which jarred with the academic and experimental tone of other speakers. However, with Adobe producing the tools that underpin data-focused marketing, it was time to tackle the nitty-gritty. That said, Jamie reiterated some messages already shared: engage with your audience; “embrace rocket science” (I like that one); connect the dots between your teams and between the physical and digital worlds; measure the wealth of your data; test, optimise and personalise; and bring your data together. Advocating for his products he suggested taking the Adobe Marketing Pro test, which assesses an institution’s capabilities within its sector.

Talking of “interlopers”, Charlotte Richards, Head of Business Partner at News UK, reminded the museum professionals in the audience “…you’ll need new types of people who will be new to the sector – nerds!” She also advocated failure; “it’s OK, just get going and then re-evaluate”. Both these statements were later questioned by audience members who were sceptical that technology professionals (and graduates with high-earning potential) would opt for the culture sector and its endemically low pay. Still on money, it was pointed out that institutions that need to justify every penny of public or charitable funding don’t enjoy the luxury of failing. Rob Jackson of DBI (another speaker from the private sector) countered by suggesting the culture industries entice geeks at grass roots level, setting up internships, employing students and starting projects with universities. Jamie from Adobe added that attracting graduates into technology businesses is also an issue as they can earn more in the financial sector. Charlotte countered that graduates are excited to “work somewhere they can make a difference because they could be somewhere very anonymous”.

Another question mentioned visitors and was aimed at Chris from The Guardian: “How far can the personalisation of content go?” His suggest that a site made relevant to the visitor can create loyalty; “start small” then “customise” by identifying “clusters of behaviour”. Charlotte introduced the “anti-algorithm…don’t be so tailored that visitors only get what the algorithm thinks they want”. Chris admitted that editorial teams at The Guardian “want to edit” and not just let a program constitute a webpage for a reader based on data, however well tailored it might be. He threw a question out to the audience: “What is engagement and how do you measure it?”

Now that’s one to ask an audience of museum professionals….

Charlotte answered: “It depends on your objectives, at News UK it is clearly commercial, but in culture it might be different?” One suggestion was that the Internet of Things, which should bring online and offline closer together, would reveal how people use digital resources and whether they are a “sneaker, peeker or seeker”. Chris shared The Guardian’s “three key metrics”: reach, the number of people we get to; loyalty, how many visits do they make; and engagement, how long do they spend on our website.

The afternoon sessions kicked off with “Showcases from the ‘Digital R&D Fund for the Arts’”. First up, Joeli Brealey, Project Manager at Future Everything, the developers of ArtsAPI, described how their program reveals how well-connected an arts organisation is, to locations, sectors (public and private), and people, using data from staff emails. After sorting out “tricky” issues around privacy and ethics the information gathered has proven helpful not only to marketing departments but for impact assessment too. “Data pulled can reveal strengths an institution didn’t even know it had”. It can show: the flow of power in and out of an organisation, which translates into influence; “density”, meaning the speed at which information and ideas move; and participation, with overlaps and interactivity revealing productivity. On its website, the CEO of Future Everything, Drew Hemmett, explains: “ArtsAPI combines the deep insights generated through a technique called Social Network Analysis, or SNA, with the power of online software tools and linked open data”. Here I’m reminded of Bruno Latour’s Actor Network Theory, if only in linguistic terms, but it might be interesting to compare…

Cimeon Ellerton, Head of Programmes at The Audience Agency, presented along with Alison Whitaker, a Data Scientist in Residence who’s worked with theatre, opera and arts companies. She explained how she engages staff with projects beyond their day to day activity while doing ethnographic research into what happens when people and data mix. The aim is to communicate across the “reverential gap” that traditionally separates domains of knowledge and expertise. Cimeon explained how a data scientist can intervene to fill that gap by “wrestling” data and making it useful. Again, the question was: “What can we ask of our data?”, stressing that “…data-informed decision making is not a replacement for (regular) decision making”. Continuing to close the gaps, John Knell, Director of the Intelligence Agency suggested that a digital R&D programme have three partners — tech, culture and academic — and spoke about “Culture Counts”, a platform developed to support the use of “quality metrics”, something that Arts Council England is promoting. Standardising big data, using different groups to evaluate (peer and public) and accepting that “the language of quality” is not universal, is part of Culture Counts process of linking data and culture. John mentioned how an institution such as the V&A represents a unique cluster of curatorial and creative professionals, whose opinions are valuable to peers in London and further afield. For example, even knowing what private views staff were attending could be considered valuable data.

In the Q&A, chaired by Joeli, the audience questioned if these data tools might help institutions take creative risks, as in, could this new knowledge of audiences inform programming? An adjunct question asked about the challenges to pooling data, could there be privacy issues? Answers from the panellists suggested that these issues were already being tackled and that both deep analysis of data and good handling practices meant information and meta-data could prompt content change and be shared.

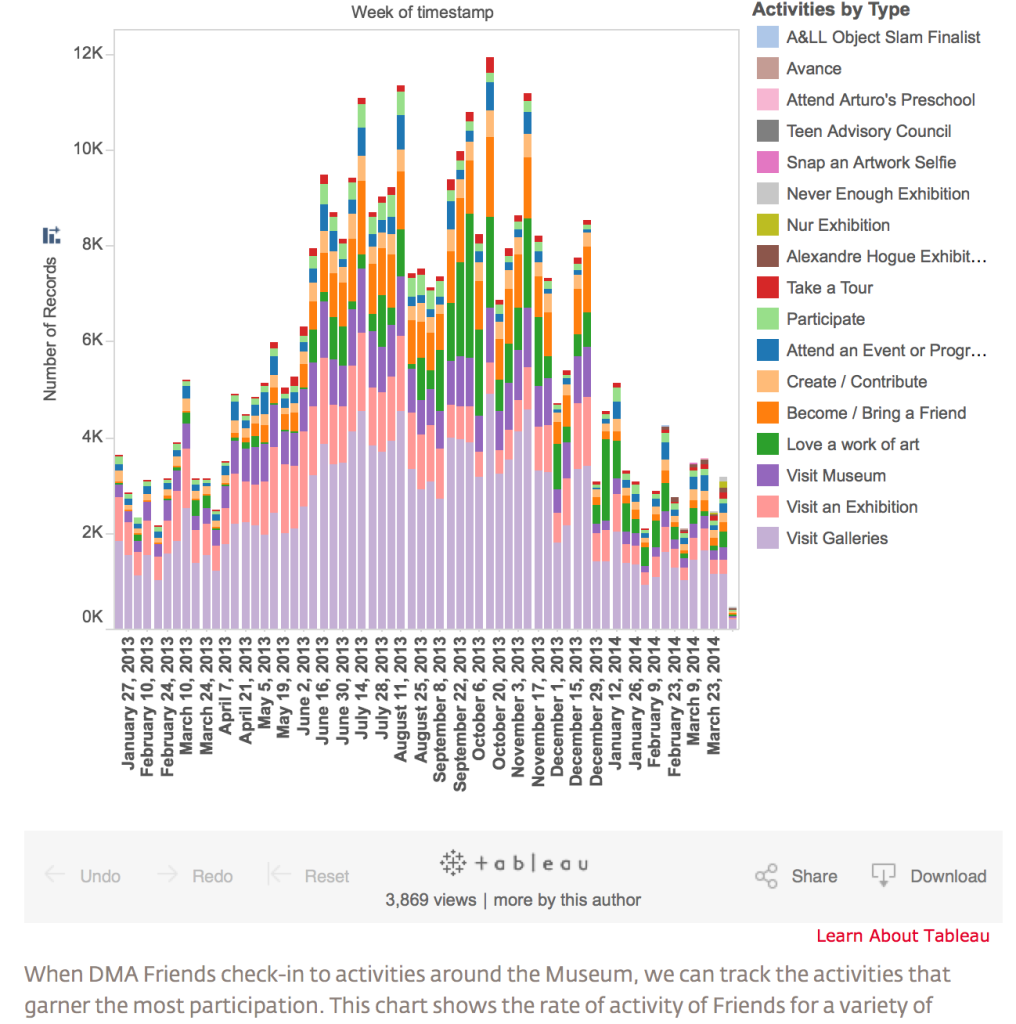

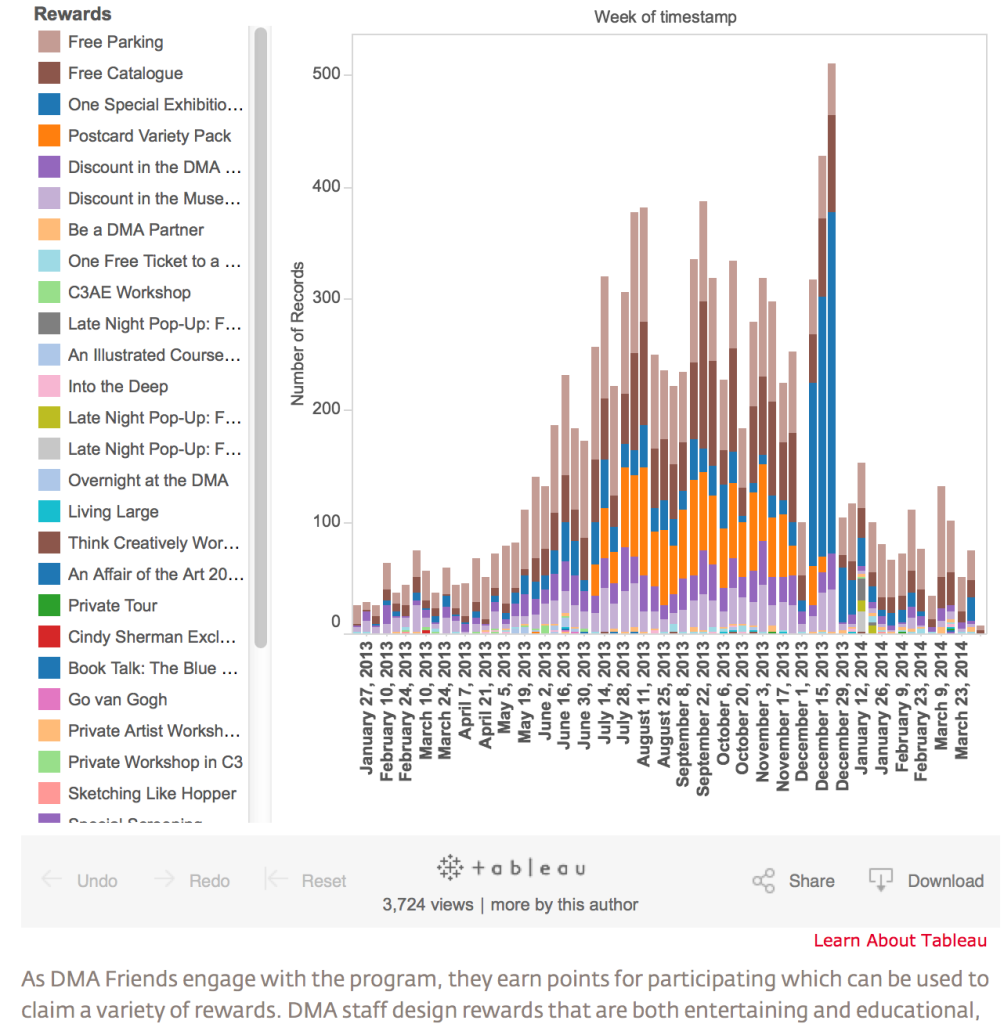

Next, the lecture theatre’s big screen lit up for a Skype chat with Shyam Oberoi, Director of Technology and Digital Media at Dallas Museum of Art, showing off DMA’s innovative Making Friends kiosk. A free-entry museum, DMA needed to know more about its visitors and set up an iPad-based sign-up and rewards system that offers pay-back for regular visits. Attendance rose 48%, with 97% of new Friends being first-time visitors. Now the Museum attracts 10% of the regional population, up from 7%. Shyam revealed that the system is being shared with other museums in the US, and that because it uses “off the peg” systems, MailChimp and Amazon Web Services (AWS), it costs very little, about the same as a microsite, plus Shyam’s giving the code away for free!

The final session, “Joined up thinking: linked open data” brought the BBC, Google and the Open Date Institute to the stage to demonstrate some of the economic, social and ideological implications of data use. Pushing the boundaries of “broadcasting” into digital delivery, the BBC’s RES project (Research and Education Space) was introduced by External Relationships Manager, Richard Leeming. Essentially, the aim is to link up existing resources into a digital library of the UK’s cultural assets. A fundamental refocus, this project questions the commercial imperative of the Internet and challenges the editorial control of US corporations. Progress towards turning data sets (silos of information housed in separate institutions) into “Linked Open Semantic Data” is already underway with the British Museum using CIDOC’s Conceptual Reference Model to share records in a computer readable format. A webpage introduces the project by contrasting it with the Museum’s public-facing Collections Online webpage; it’s the same but different…same data, different audience, different format, different tools. Richard went on to explain how data and content are separate things, and how computers need to better understand content. RES offers interested parties access to masses of content and code, including the API, application program interface, which is necessary to create software and GUIs (graphic user interface); these resources can be used to build new digital experiences. Richard also mentioned projects and reports such as The Digital Public Space (by Future Everything) and the agenda-setting report from the Warwick Commission on the future of cultural value (published February 2015), titled Enriching Britain: Culture, Creativity and Growth. In partnership with organisations such as Research Space and The Creative Exchange the BBC and the British Museum, among others, are working towards a fundamental re-evaluation of the Internet, foregrounding culture, education and heritage, imbued with the ethos of sharing and open access, in a sense, reigniting the original remit of the Internet.

Screen Shot explaining how to search the British Museum’s online collections; although typical of a public-facing graphic user interface it does give extra-useful tips on how to search

Screen Shot of the British Museum’s webpage to another version of the online collection, as “Linked Open Semantic Data”.

Coming to the end of the day, filling the statistical gaps in our knowledge, Benedict Glynn, Strategic Account Manager at Google, gave us a whole lot of big numbers, possibly in an attempt to win the audience over to the idea that Google is doing “good”; in the end though it sounded more like a sales pitch. However, it’s worth repeating that Google invested $3.5 billion in infrastructure in the fourth quarter (“Q4”) of 2014. Benedict suggested that “…if you want to innovation you have to be able to fail, and have quick access to data, in order to iterate, fail, iterate.

Hannah Redler of the Open Data Institute (previously a curator at the Science Museum) advocated for the role of artists in all of this. Artists in Residence programmes function like “the canary in the mine” (hopefully minus the death toll) as they ask key questions such as, “what is data?” and “how does it reflect on our lives?” Carrying the torch for “social, ethical, political and aesthetic implications” and representing “the real world” sounds a lot to handle, the implication being that scientists are free to ignore these things. Hannah advocated for “data anthropology” putting humans at the centre of data, and collaboration between art and science, to share new skills and present results through exhibitions and performance. A positive note indeed…

In the final panel discussion, moderated by Beth Bate, a Clore Leadership Fellow seconded to the British Museum, Hannah tackled the elephant in the room, the ability to fail, advocated by both Google and Adobe. She pointed out that the funding model for museums (and other government- and charity-supported cultural institutions) doesn’t allow for failure, because in order to win funding you have to prove that a project will work and then show that it did. That was backed up by a comment from the audience, made by a BBC journalist, who agreed that the BBC doesn’t like failure either. Hannah had the last word by reminding us that Artists in Residence programmes could be the answer, as artists are funded to be experimental, and therefore are free to fail.

By the end of the day I realised that I’d experienced a unique learning opportunity, with the bonus that it was thoroughly engaging and enjoyable. That said, it’s only after re-reading my notes (I’m a fast scribbler) and following links to organisations and publications mentioned by speakers that I fully appreciate how germane this event is to my thesis which, brings together design, museums and archives; explores traces of temporary exhibitions; advocates for institutional transparency; and considers the widest influences of cultural institutions starting from their physical and virtual presence. Design museums may have a unique role to play within this arena of digital culture. Design thinking; experimental and cross-disciplinary residency programmes; multi-disciplinary teams and skills sharing; presenting results in exhibition formats that explain “difficult” concepts to wide audiences; instigating innovative learning experiences; over and over, speakers advocated such strategies. When it occurred to me how familiar much of it sounded — putting aside the computer-lingo — I realised that it is because design museums are already dealing with the implications of a third industrial revolution and the dematerialisation of design by exploring ways and means of describing and presenting systems and processes to diverse audiences. And, possibly, they have the widest “audience spread” of any other museum type. Using their privileged position, at the nexus between culture, creativity, commerce and education (at all levels), design museums could organise, host, network and disseminate experimental digital and data projects to expand our understanding of and access to data, whether you’re you work in the culture sector or are simply a member of the public interested in how their data is being used.

This event was discussed on Twitter using the hashtag #BMdigitalconf.