Design Museums for the 21st Century; a round table discussion

Trapholt Museum and University of Southern Denmark

Kolding, Denmark

23 January 2014

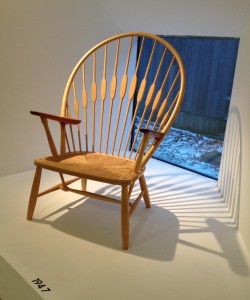

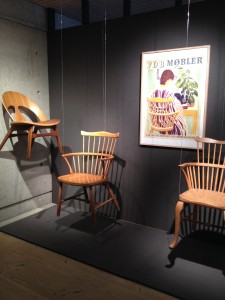

When your PhD supervisor tells you to go to Denmark in freezing January, you go; the icing on the cake was that it started snowing as we sat in the Trapholt Museum’s meeting room, with its giant picture window, and everyone went “aaaahhhh”. The Museum is housed in a playfully modern building, boasts an unrivalled collection of Danish chairs and is next door to Arne Jacobsen’s summer house (sadly I didn’t get inside, this time), so that made up for the weather. I also got to see the thought-provoking and unprecedented touring exhibition, Out to Sea? The Plastic Garbage Project, which seemed totally appropriate in a country that loves fish.

My reporting of the round table is from my notes, with additional my comments; where they are short and in the same paragraph, they’re in [square brackets].

My supervisor is University of Brighton’s Professor of Design Culture, Guy Julier, and he is also Visiting Professor at University of Southern Denmark. He’d gathered his grad students from Denmark and Brighton, along with “expert witnesses” from the museum world in Denmark and the UK, to discuss design. Guy opened the proceedings by telling us that design museums were “mushrooming”. He counted 45 European design museums with more projects for new, expanding and relocating institutions still in the pipeline, mentioning that Mexico City’s MUMEDI, tripled its visitor numbers by rebranding as a “design museum”. He talked about the tension in museums between the contemporary and history, design and design history, and that a contextual approach to design in museums was the way forward, mixing the excitement of innovation with the pragmatism of solving problems, and heritage and continuity with new technology and innovative design fields. Finally, he pointed to the Index Awards (a Danish initiative) as evidence of design shifting away from a fascination with “heroes”. […and by extension, a recognised canon?]

The next speaker, Kieran Long, Senior Curator of the new Contemporary Architecture, Design and Digital team at the Victoria and Albert Museum, told us that every department in the Museum collects contemporary design. He was interested in what contemporary practitioners do with the V&A, admitting that engagement across the disciplines was uneven. His team has three fields of interest; architecture, product design and digital design. [One question: by specifically naming “product” does does the team exclude furniture and graphics, for which there are well established departments?] He recognised that the V&A’s “power” is in the collection, where expertise and research is concentrated; because of this, he came up with a new collecting policy, by turning it on its head. The world is moving too fast to go through the traditional long-form process of collecting, which entails waiting until an object has “a provenance”, and he used the “Christine Keeler” chair as an example. He went on to suggest that contemporary collecting should reflect the speed of global news networks, capturing events as they happen; for example, a pair of Primark casual trousers (aka fatigues) were collected to represent the Rana Plaza disaster in Dhaka, 2013, when a building housing garment factories collapsed. The (fast fashion) trousers collected may not have been made there but they stand-in for the manufacturing system. [How those stories are told within the gallery and by extension, on the museum’s websites and social media is crucial to making sense of this type of collecting, which is a point I make in a previous post, here].

When asked if this sort of collecting means that the Museum is now concerned with “campaigning”, Kieran said no, it’s more about telling the truth through objects. He’s named this process Rapid Response Collecting [borrowing lingo from the emergency services]. Kieran went on to describe the rigorous research process, which included travel, interviews, legal research and customs documentation, that surrounded the collecting of Cody Wilson’s 3D printed hand gun, The Liberator. [That said, why was Kieran interviewed in the media coverage, rather than Louise Shannon, the Curator of Digital Design who actually acquired it]. Long suggests that the 3D printed gun made it onto the news because the V&A collected it, and that it cannot be deaccessioned.

The Collections Management Policy, Victoria and Albert Museum, 2009, Version 1.1, is available online as a PDF and gives several reasons and means for disposal of, or in museum speak, the deaccession of objects. (Industry standards for objects transiting in and out of museums is spelt out in SPECTRUM: The UK Museum Documentation Standard, promoted by the Collections Trust, the professional association for collections management). for the I bring this up because another acquisition, a box of Katy Perry false eyelashes, which Kieran pointed out were collected with “all the documentation” (meaning?), might not be of interest to V&A visitors once Perry is out of the limelight. Kieran described how the object was manufactured, the way hair used in the eyelashes was sourced and the working conditioners of the artisans who made them. That story in itself is bizarre and fascinating, but the system that created the need and means for producing such an product could also be part of the exhibited story, e.g. celebrity culture’s tie-in with fashion styling and its exploitation by licensing companies, solicitors and agents and mass retailers, which facilitate the attachment of Perry’s name (or whoever) to generic goods. Her endorsement is everything.

Anne-Louise Sommer, Director of the Design Museum Denmark in Copenhagen (which I visited the next day), talked about a shift in how people are using museums, as part of a civic society; she suggested “People create design and design creates people”. She presented a considered argument for the multi-dimensions of design, encompassing crafts and industry, and the role of design museums in providing historical perspective and raising the quality of designed products by way of education. Her Museum is tasked with promoting design knowledge and insight to a wide audience, and this means “good design”. With a new strategic plan launched in 2013, the range of activities are defined as cultural, industrial and educational, and while the V&A was acknowledged as the “big sister” of the DMD, Anne-Louise pointed out that she has only three curators to do the work, and that most design museums are on this scale (rather than the V&A’s). Until last year the Museum had been arranged chronologically, with no objects post-2000. The shift has ditched the idea of a permanent collection, instead instilling “semi-permanent” exhibitions and displays on show for two to three years. There are three strands to the new initiative; furniture, fashion and “Danish Design Now”, all intended to show off strong Danish traditions, and are proving popular with the Museum’s audience (visitor figures have risen year on year). The big question is how to exhibit the everyday,to convey the multifaceted experience of objects, to be a multi-sensory museum, without allowing visitors to touch objects. The aim is for the Museum to be recognised as one of the world’s leading design museums by 2020.

Another of Guy’s doctoral students, Sabina Michaëlis from the University of Southern Denmark, spoke about the commercialisation of the design museum, with its roots in MoMA’s series of Good Design exhibitions (1944-1956) that were jointly arranged with Chicago’s Merchandise Mart, a giant showroom of showrooms. Such commercial cross-overs canonised brands; she quoted the epithet “You’re nobody until somebody sees you at MoMA!” Sabina mentioned how, in the first review of London’s Design Museum in an academic journal, Barbara Usherwood (Design Issues vol.7, no.2, spring 1991) questioned the sponsorship deal with Sony that put their TV monitors in the gallery, ostensibly as display items, but into the gallery they went. She also mentioned a row that took place in the Danish media about what constituted a “design classic”, the “must haves” for the Museum. Sabina suggested that because there is an overlap between commerce and design: “…design is now a label for selling the museum”, and called for sponsorship to be discussed and transparent, as part of the discourse of design and design museums.

Igor Calzada, whose background is urbanism and innovation rather than design, said that despite crises in “funding, audiences, and meaning in art and architecture”, he called for the museum to be reconfigured as a “critical social innovation centre”. Because the pace of crisis varies across the EU, and an institution is affected by the territory it inhabits, every museum has to find its own business model, but that museums and universities can act as catalysts, scanning for and shaping ideas for all stakeholders. This necessitates collaboration between public and private – activists, entrepreneurs, bricoleurs, hackers, co-creators and pro-sumers. The museum becomes a social, community-driven research centre asking questions like, What is a smart city? Rather than the collection being centre stage (after all, the meaning of objects shifts), curators need to step up but be less concerned with their own specialisation. In this way the museum becomes a system, moving from ego-centric to team-work.

My own positional statement stressed “I’m not a museum person” but come from design publishing and higher education. Part of my practice is to be self-reflexive, my role is to be an outsider looking in. Mirrored at an institutional level, this could suggest an inside/outside position for design museums, within/beyond the consumer-led capitalist society. From this position, the museum could acknowledge and explore its role in forming definitions of design. I explained that my project involved observing a design museum going through a process of redefinition, which has provided an opportunity to challenge preconceptions of success and failure in terms of programming. Looking closely at a “difficult” event in the history of a museum can prompt questions about methodologies, perceptions and aims; however embarrassing and painful these instances of “institutional friction” might be, reexamining them (using academic rigour and ethical sensitivity) opens the museum to new levels of self-awareness and transparency, and reveals preconceived ideas and hidden agendas.

Such self-reflection also highlights the uniqueness of each design museum, embedded in urban, regional and national scenes that are reflected in collections and the knowledge and expertise of its personnel. Specificity may be on offer but multiplicity is the goal. All design museums are chasing diverse audiences and must offer a mix of scholarly exhibitions, practical demonstrations, professional events, and edu/tainment for all ages. Perhaps one way of mixing specificity and multiplicity is to network between institutions, to share expertise, collections and resources. That might not be easy, even in a politically-correct arena, as traditionally institutions have been conceived as treasure houses, both of objects and connoisseurial knowledge. The alternative is a predictable “streamlining” of design into a hegemony of blockbusters, generated by a few museums and toured to the rest.

Ending on a positive note I pointed to alternatives that are already flourishing: the V&A’s annual collaboration with the London Design Festival turns the museum into an urban cultural “hub”; repeat shows that create a legacy of community, for example, the London Design Museum’s Designs of the Year and Designers in Residence. The interactivity of nominating, voting, workshopping, networking and seeing new talent supported and promoted, instills trust between audience and institution. Design museums are in the enviable position of being able to present and promote change, perhaps even becoming a third space for the third industrial revolution. [See more positive instances of cross-institutional collaboration instigated by the MUSCON network, explored in a post, here.]

Guy questioned, why should museums be these social innovation spaces, suggesting that interaction with objects may be the key; perhaps institutions could be less like “museums” and become more “interactive”. Conversation ranged around, questions and statements such as, right now content is not interactive enough, but volunteers prompting audience participation, could be the answer. Mention was made of “github” and “crowd-sourcing” and a new type of hybrid curator, with a mix of skills and experience, all of which could increase the agency of audience and staff, with the aim of helping visitors make choices, in a space that is both public (welcoming) and private (safe).

For more about Guy’s work at Design Culture Kolding, see his blog; and for his write up of this event, his post, “Contemporary Design Culture and the Design Museum: Challenges and Opportunities”, here.

I wrote up this event to add background to another post that mentions the V&A’s RRC initiative, here.

All photographs taken by Liz Farrelly, on an Apple iPhone 4S.