40 Years On: the Domain of Design History. Looking Back Looking Forward

The Open University

Berrill Lecture Theatre

Milton Keynes MK7 6AA

22 May 2015

Here’s an edited and slightly expanded version of the paper that I gave; I’d like to thank Dr. Elizabeth McKellar for organising the event and for inviting me to participate. The images are from my PowerPoint presentation.

Since 2011 I’ve been working on an AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award, which partners University of Brighton with London’s Design Museum, so this paper comes out of a larger work-in-progress and started life as a search for mentions of the Design Museum in academic journals.

A bit of background; from thinking that my application for this award was a random act of “career development”, I’ve come to realise how important the Design Museum (“upper case”, meaning this specific institution [capitalized in this text]) has been to my design-focused career spanning teaching, publishing and curating. I started on an Art and Design Foundation Course in 1982, the year in which the first incarnation of the Design Museum, the Boilerhouse, opened in the basement of the Victoria and Albert Museum. During my Art History degree at University of Sussex it was exhibitions at the Boilerhouse – on Memphis, Issey Miyake, Handtools and British Youth Culture in particular – which enthralled me to design, from the objects on display, to the installation and display, and even the much-maligned white-tiled gallery. While the Director of the Boilerhouse, Stephen Bayley was considered “very bothersome” within the V&A and aimed to discourage people “wandering in from the V&A” (as he put it), I wandered the other way onto the V&A/RCA History of Design MA. Graduating in 1989 just as the Design Museum opened in its new Thames-side location, my work as a design journalist included reviewing exhibition; not always nice, not always nasty. For the last four years I’ve been: invited to nominate for Designs of the Year; observed the goings on in the café (not that this is a sociology of the Design Museum); talked to staff (on and off the record); enjoyed sporadic access to an “under construction” archive; visited every exhibition; dealt with the contradictions of a Supervisor who is also top of my list of “interviewees” and a very busy museum Director; and witnessed the museum prepare for its next phase.

That reflexive turn aside, I’ve come to realise the importance of design museums (“lower case”, meaning all museums of design) in the formation of the discourse of design. But, I’ve worried about the hint of futurology in this project’s title, which made me question how looking back to see the future might work when dealing with a relatively recent phenomenon, a new museum type. When reading about another newish phenomenon, the Internet, I found a useful signpost from Manuel Castells (2001).

“I start with the historical and cultural process of the creation of the Internet because it provides the clues to understanding what the Internet is, both as a technology and a social practice…The history of the Internet helps us to understand the paths of its future history-making”. Paraphrasing Castell’s quote to fit my question, by looking at the “historical and cultural process of the creation of” the Design Museum and design museums (upper case and lower case), we might “understand the paths of its future history-making”.

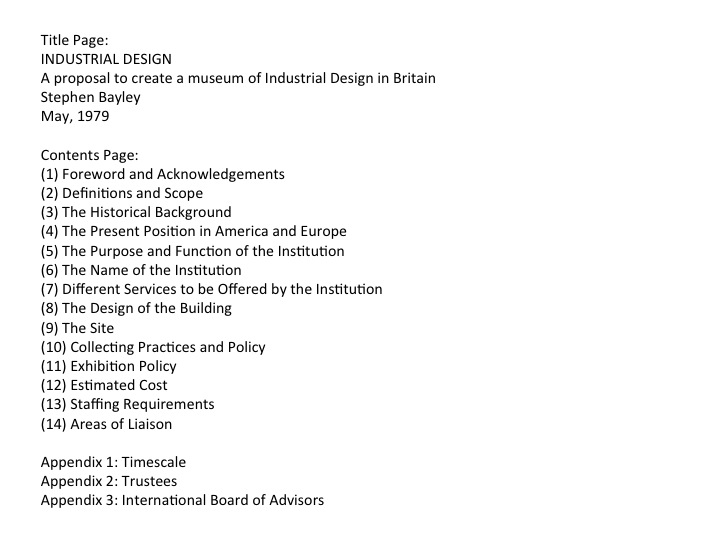

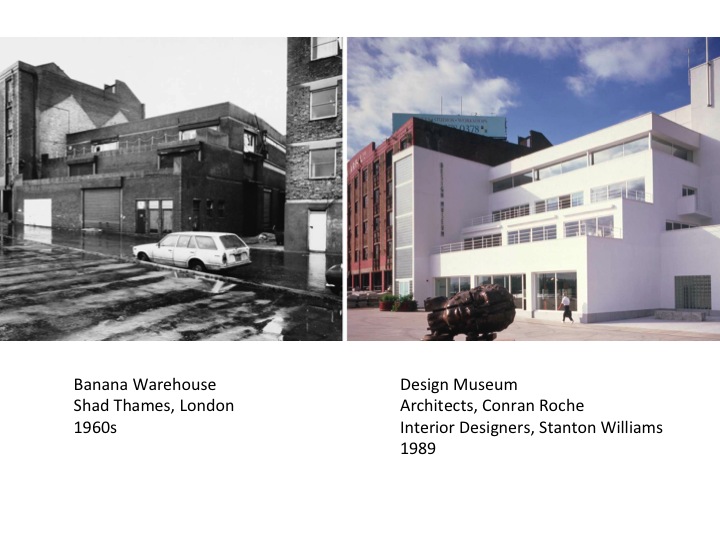

A bricks and mortar institution is more static than the Internet, but, untypically, London’s Design Museum (my case study) has experienced some seismic shifts – of location, funding and personnel – since in 1978 the first speculative feasibility report was commissioned by Terence Conran (not a Sir then) from Stephen Bayley (completed in May 1979).

This alliance between Bayley and Conran was brokered by Lord Paul Reilly (retired Director of the Design Council) and is documented in the Paul Reilly files at the V&A’s Archive of Art and Design in Blyth House. Bayley was a contributor to the Open University’s A305 History of Architecture and Design; and the “Museum of Industrial Design in Britain” was to be sited in Milton Keynes, with the help of Fred Roche, a member of the new town’s planning team and partner to Conran in the architectural and planning consultancy Conran Roche, which eventually designed the current museum building at Shad Thames.

This yellowing document represents an early step in the “process of creating” the Design Museum and establishes a link between the Design Museum, the Open University and Milton Keynes (most appropriate for today’s proceedings); it also sites the museum within a developing discourse of design by flagging-up the importance of a name, in this case, the “Museum of Industrial Design”.

Jumping to the future; since 2006 the Design Museum has been undergoing its most seismic shift yet, with the planned relocation to the former Commonwealth Institute in west London; the opening date is set for September 2016. The museum will triple in size, mixing its “kunsthall” pay-to-enter temporary shows with free-to-access permanent displays, designers in residence studios, open collections and archives, a café, restaurant, rooftop bar and shop.

Screen-grab from the Design Museum’s website, showing a rendering of the interior of the new museum, designed by John Pawson.

…and Culture. Reaching the end of the scrolling page, social media icons prompt the website user to share content.

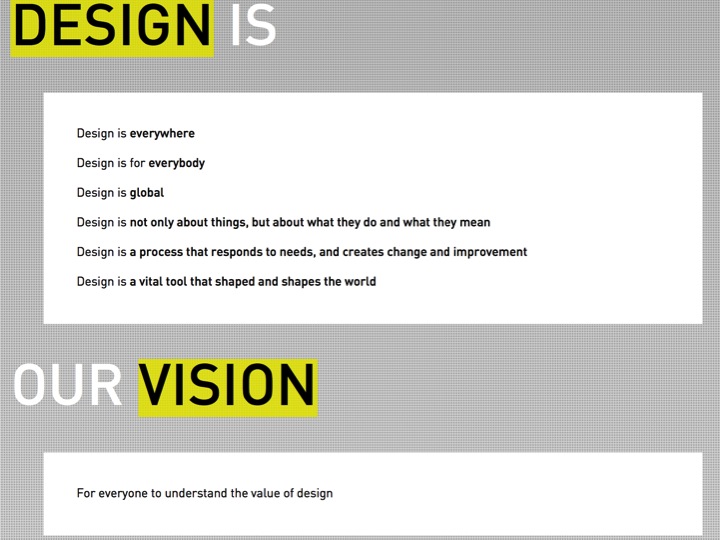

The first live-to-the-public element of the move is the newly “responsive website”, the museum’s main channel of communication; designed by Dutch agency, Fabrique (which also created the Rijksmuseum’s website), it’s also won a Webby. Typically in the museum world, such a comprehensive redesign includes a revamped “mission statement”. Having read a fair few mission statements from design museums, I’d suggest that underpinning these evolving “messages” is one constant, a need to define design. Certainly, design museums aren’t alone in that obsession; the question “What is Design?” also cropped up in A305, back in 1975. But, in the context of a design museum, such a definition affects its entire offer.

There is a rich academic literature exploring museums that collect, display and interpret designed objects, from Anthony Burton to Linda Sandino at the V&A, and Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach to Mary Anne Staniszewski at MoMA, but even though the design museum as a standalone “museum type” is booming, it remains underrepresented in the academic literature of both Design History and Museum Studies, which may suggest that it sits awkwardly beyond or between the critical territory of these disciplines. Notable exceptions include the last chapter of Professor Cheryl Buckley’s Designing Modern Britain, and, as noted by Professor Jane Pavitt, design museums regularly crop up in V&A/RCA MA dissertations.

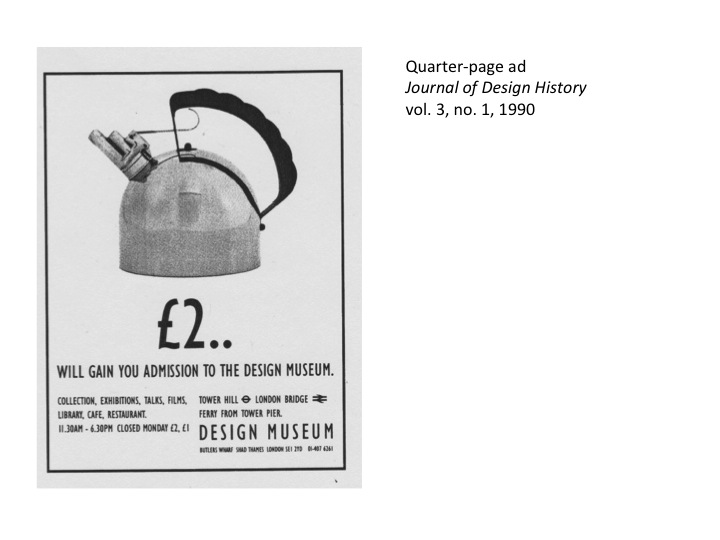

A media search for the Design Museum within the literature of Design History started with the Journal of Design History, the earliest mention being an ad for the museum, featuring an iconic object, Alessi’s 9091 kettle designed by Richard Sapper, and a reminder that this private museum is a paid attraction. Apart from a few nodding references (in book reviews) to personnel associated with the museum, no reviews of the museum or its exhibitions appear in the Journal of Design History. (I’m still trawling through, so this might change…)

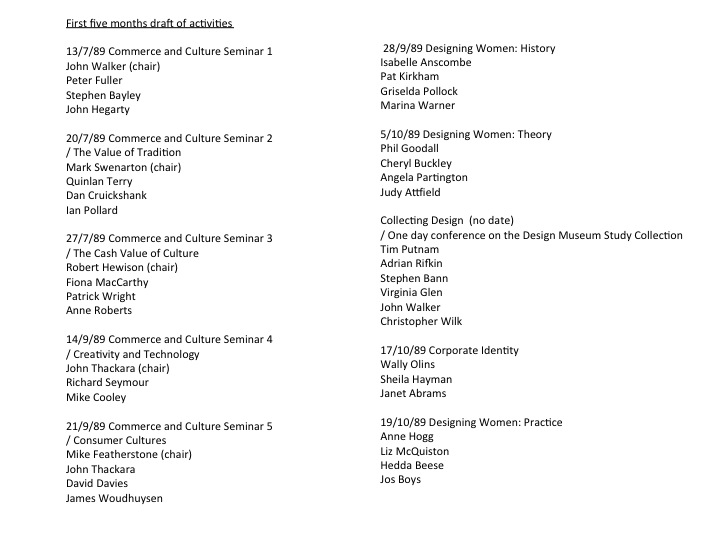

Someone at the museum thought it a good idea to market the new venue to Design Historians, and academic debate was welcomed, evidenced by an impressive programme of seminars around Commerce and Culture, the first exhibition in the Thames-side museum. This list of proposed seminars is from the museum’s archive, found at the beginning of my research in 2011. In 2012 the archive was relocated and some of the newly boxed material was re-boxed. At the time of this lecture I had found no further evidence of these events, but the following week I uncovered early issues of the museum’s monthly printed Bulletin. Judging by the published, printed version, the typed sheet was a “wish list”: approximately 40% of the speakers were replaced by other names; the three Designing Women seminars didn’t happen; extra events related to exhibitions on French and Spanish design also featured Design Historians; and the Collecting Design event became a one-day conference on New Museology, featuring Peter Vergo (University of Essex), Eilean Hooper-Greenhill (Leicester University), Stephen Bann (University of Kent), Colin Sorensen (Museum of London), Virginia Glenn (Royal Scottish Museums Edinburgh) and Charles Saumarez-Smith (V&A/RCA). This intensity of critical debate (signaled by both the wish list and the actual staged events) in the first months of the Design Museum proved difficult to sustain; events programming is resource-heavy requiring time, space, personnel and funding. According to the Bulletin, planned events happened once or twice a week from 1990 to 1992 but reduced to one or two a month through 1993 and 1994.

Looking further afield for Design Historians writing about the Design Museum, two articles – Barbara Usherwood’s published in Design Issues and Deborah Sugg Ryan’s in Home Cultures – stand out as exemplars of how to do Design History not just in the museum but on the museum.

And, while I’ve been busy in a number of archives, looking for mentions of the museum and reconstructing its programming from curatorial and communications files, the issues raised by Usherwood and Sugg Ryan, in these two short articles, have continuously informed my reading and research.

So to the articles: Usherwood’s detailed description of the newly opened Design Museum transports the reader back to a long-gone version of the renovated warehouse in Shad Thames, which is in effect, a skin-deep simulacrum of modernism with ocean-liner decks, a faux-corporate reception desk and pristine marble and white interiors.

Usherwood’s article opens with an off-kilter view of the entrance that promises an energetic hand-held-video type of tour, but any enthusiasm for “spectacle” is checked: “There will be few surprises…The entire museum is a paradigm of modernist style”, which in 1989 was hardly news. Usherwood makes the link between funding and influence much as Duncan and Wallach do when describing the Louvre and its succession of French rulers. In this case the Conran Foundation has “largely funded” the museum, so house-style is Conran-style.

After getting us in the door, Usherwood asks three questions of the museum: “What is it saying about design? Which audiences does it address? [and] Whose purposes does it serve?” While answering these, she acknowledges “the circular nature of the funding…Conran’s own missionary-like efforts in bringing good design to British homes are being used to finance a Design Museum”. Mention of good design brings up Fran Hannah and Tim Putnam’s notion of “covert aestheticism”, which they define as “‘taste operating as an unknown and therefore arbitrary determinant of what is selected as good or significant design’”. Usherwood thinks that the exercise of such unacknowledged good design/good taste has resulted is a very partial Study Collection, translating into a newly-minted canon, dominated by great white males – no women are included – and lacking all promised contextual material. Of course, every design collection is “partial”, there is no way to collect each-every-all designed objects, but Usherwood points to the museum’s “limited concept of design” as part of the problem.

She goes on to suggest that the temporary exhibitions programme could temper this prejudice. If preparation for exhibitions includes an opportunity for research to be carried out it could produce a “variety of perspectives on designs and their meanings”. Mainly though Usherwood is disappointed by the museum: because of its too-cosy relationship with sponsors, which might set a precedent for corporate funding; because its focus is too narrow and commercial (but remember its original aim was only to be a Museum of Industrial Design…); because of an emphasis on aesthetics; and because of a lack of transparency and rigour (she criticizes Bayley for not adequately defining “culture” in Commerce and Culture); because it undermines it stated aims of contextualizing designed objects; because it stresses innovation and ignores sustainability (Usherwood is well ahead of the curve on this issue); and because it is gender and class biased (another criticism directed at the thesis of the opening show, Commerce and Culture).

For all her criticism though, Usherwood demurs to provide sources of the quotes she includes, referring throughout to museum “publicity”; but is that public-facing gallery guides or privileged press releases? Either way, the ephemeral nature of the museum’s communications is highlighted. Some of that material has been saved and is now in the museum’s archive, but it remains un-catalogued and therefore unavailable. A fully accessible archive is promised in the schema of the new museum and this improved access is vital if the museum is to become a location for research, including the study of its own history.

By contrast, Sugg Ryan’s review of Constance Spry: A Millionaire for a Few Pence quotes plenty of on-the-record sources as more than 40 newspaper and magazine articles were published in response to a very small, last minute, low-budget exhibition about a mid-century tastemaker, the forever enigmatic Constance Spry, although only Sugg Ryan’s article qualifies as “academic”.

On a budget of just £2,000, the exhibition was hastily assembled to fill a programming gap. An email exchange between the Director, Alice Rawsthorn, and Conran dated 24 and 25 November 2004, discovered in a file marked “Conran Foundation Collection 2003 Thomas Heatherwick”, may offer a clue. Although the Spry exhibition was almost over (it ran from 17 September to 28 November 2004), the exchange (which includes indications of deleted messages) mentions a ready-made exhibition from Issey Miyake, which the Chairman of the Board of Trustees, James Dyson, had agreed to stage, but without consulting the Director. Rawsthorn reiterates her “no” to that exhibition, and although no dates are mentioned such a conflict over scheduling may have led to an empty gallery space that needed filling. To put the size of the Spry exhibition into perspective, Commerce and Culture was budgeted at £250,000 (according to the design brief from the file “Commerce and Culture”).

Although it was more a display than an exhibition, the presence of Spry in the museum prompted Conran to tell The Guardian that it “betrayed” the museum’s founding principles of “exploring the industrial design of quantity produced products”. Fourteen years on from Usherwood’s article, what she described as “a limited concept of design” was still foremost in the mind of the museum’s founder, one of the most powerful players within the museum.

Sugg Ryan quotes Conran’s “Letter to the Editor”, and four more newspaper stories in her article, because along with reviewing the exhibition she presents and considers the media reaction it sparked. Like Usherwood, Sugg Ryan is disappointed: the Spry show is a missed opportunity for the museum to consider “nonprofessional” designers and influential but overlooked women working beyond the established canon of modernism. The exhibition could also have been an opportunity to consider “individual creativity and design” in response to what Sugg Ryan identifies as a new emphasis in Design History, a “shift from production to consumption”. And, the fact that Spry actually made it into the museum is overshadowed by both the row and what Sugg Ryan considers to be poor quality display and interpretation. She points to: a paucity of objects, environments and flowers that could better demonstrate Spry’s approach; the absence of information on Spry’s wider career and personal life (she was much more than a “mimsy” flower arranger); and over-long text panels and dim lighting that made it difficult to enjoy the exhibits. Sugg Ryan concludes, “The exhibition promises much more than it delivers…”

You may think, why all this fuss over a mediocre display of photos and vases in a tiny space in the far corner of a small museum? Curator Libby Sellers and Director Rawsthorn kept silent in the face of criticism, perhaps out of surprise at the reaction generated by the show, or because they realised something else was at the root of the criticism? While the show’s critics were defending their perception of the museum, they were inadvertently demonstrating another agenda. Criticism of the Spry exhibition and the museum’s wider programming hinged on the accusation that it demonstrated “style over content”; but such an assessment does not match the museum’s actual offer at the time. Looking at the show, as Sugg Ryan did, through the lens of the extensive media coverage, it could be suggested that Spry was hi-jacked as a means for powerful individuals within the museum to display disapproval of any redirection of “their” institution. This power struggle over the museum’s future led to Rawsthorn’s departure, which coincided with the announcement of plans to move and grow the museum under a new Director. That process of change, begun in 2006 along with the appointment of Deyan Sudjic, is almost complete.

Taken together these two academic articles present a comprehensive demolition job on the Design Museum at the beginning and end of a distinct phase of its existence, the first 15 years at Shad Thames. Invert the disappointment and it is obvious that Usherwood and Sugg Ryan had high hopes for the museum. Perhaps such hopes were unrealistic though. That the 1989 version of the museum was a decade in planning suggests the thinking that informed the programme may have got “stuck”, as the practice of Design and the discipline of Design History evolved beyond the clear-cut definition of Design that would fit the stated remit of a “Museum of Industrial Design”.

Usherwood’s title, “Form Follows Funding”, was prophetic. She explained that the Design Museum’s fortunes were dependent on the generosity of Conran and the Conran Foundation, underwritten by the value of Habitat shares that had been made over to the Foundation, and the successful redevelopment of Butler’s Wharf (owned by Conran). In the article she hints at the possibility of a funding crisis; that crisis hit hard just months after the museum opened and was felt for over a decade, seriously curtailing the museum’s ability to deliver its published programme (Design Review gallery, library and lecture theatre were closed; scaling back of events and the number and frequency of exhibitions). Ironically, the crisis cemented Conran’s power as he drip-fed extra cash and continued to exert influence over expenditure. Rawsthorn worked to diversify funding sources, which could have challenged Conran’s control. In a file named “Institution DCMS 2001-2004” [Department of Culture, Media and Sport] correspondence a series of “Funding Agreements”, “Interim Reports” and “Spending Reviews”, for the years 2002-6 demonstrate a growing collaboration; Rawsthorn was courting government support and was striving to increase the museum’s educational offer and accessibility in return. These funding initiatives were mentioned in two of the articles quoted by Sugg Ryan, so the museum must have made the information available to journalists (Glancey 2004; Sudjic 2004). Further searches of the “Communications” folders for this period might reveal a press release or two.

So what did Usherwood and Sugg Ryan expect from the Design Museum? They expected it to: engage with contemporary issues and ideas in Design and Design History; encourage research and debate; be resilient to criticism; and transparent in its operations. Judging by recent policy documents and the new mission statement, communicated to the public via its award-winning website, these expectations (amongst others) are now firmly on the agenda.

As far as my “method” is concerned, I’ve continued to use these articles to question archival material and media coverage relating to the Design Museum; Usherwood prompted me to consider the affect of funding and management on content, and to look at the museum as a complete, designed object and a producer of design. From Sugg Ryan, I realized the importance of “institutional friction” (moments of conflict that lead to change), and of decoding the museum’s “media presence” (in the mainstream press, academic journals, social media and its own channels of communication). Both articles also demonstrate that these Design Historians came to the museum with preconceived perceptions, as we all do, and examining those expectations is also part of this process of developing a new level of critical transparency.

As to whether Design History at the Design Museum is a “perfect fit” or a “culture clash”, it could be both, with equally positive results. That the museum’s offer is underpinned by research is crucial for building its reputation as a site for learning. That it is open to being “researched” demonstrates a greater degree of institutional maturity. Hopefully, the foregrounding of research and access will prompt more opportunities for Design Historians to work with this Design Museum (upper case), and by way of setting a precedent, with the widest range of other design museums (lower case) too.

References

• Bayley, Stephen (1983) “The Boilerhouse Project” International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship vol.2 no.2, 153-158.

• Buckley, Cheryl (2007) Designing Modern Britain.

• Burton, Anthony (1999) Vision and Accident: The Story of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

• Castells, Manuel (2001) The Internet Gallery: Reflections on the Internet, Business, and Society.

• Conran, Terence (2004) “Concepts of Design” Letter to the Editor The Guardian 5/10/04, 21.

• Duncan, Carol and Alan Wallach (1978) “The Museum of Modern Art as late capitalist ritual: an iconographic analysis” Marxist Perspectives 1, 28-51.

• Duncan, Carol and Alan Wallach (1980) “The Universal Survey Museum” Art History vol.3 no.4, 448-469.

• Glancey, Jonathan (2004) “Dyson resigns seat at Design Museum: Jonathan Glancey on a clash of styles and ideology” The Guardian 28/9/04, 5.

• Hannah, Fran and Tim Putnam (1980) “Taking Stock in Design History” Block 3, 25-33.

• Reilly, Paul and Stephen Bayley Correspondence in Archive of Art and Design AAD 6/4228-1992 to 6/4374-1992.

• Sandino, Linda (2012) “A Curatocracy: Who and What is a V&A Curator?” in, Kate Hill (ed.) Museums and Biographies: Stories, Objects, Identities.

• Staniszewski, Mary Ann (1998) The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art.

• Sudjic, Deyan (2004) “How these flowers caused fear and loathing at the Design Museum” The Observer 3/10/04, 5.

• Sugg Ryan, Deborah (2005) “Constance Spry: Millionaire For a Few Pence” Home Cultures vol.2 no.1, 123-127.

• Usherwood, Barbara (1991) “The Design Museum: Form Follows Funding” Design Issues vol.7 no.2, 76-87.

References to Design Museum documents from the Design Museum Archive are not included in the Bibliography as cataloguing is in progress, but the current “box” or “file” locations are mentioned in the text.