I wrote this review of an exhibition at London’s Design Museum when I worked for Wordsearch, at the time was the publisher of the design magazines, Blueprint and Eye. I was a writer and assistant editor on both titles, from 1990 to 1994, and continue to contribute on a freelance basis. We also published Design Review, a magazine for members of the Chartered Society of Designers, which ran from 1991 to 1994. (For a seminal study of the CSD see Dr. Leah Armstrong’s doctoral thesis, Designing a profession: the structure, organisation and identity of the design profession in Britain, 1930-2010 available at the University of Brighton’s Grand Parade library.)

I came across this exhibition review during the long and dusty process of locating, scanning and (still hopefully) posting as complete a record of my published design journalism as I can muster; an online archive is in the works, hence the long and inexcusable lapse since my last post on this blog. I’m thinking a lot about archives right now. I’ve planned a series of visits to the Design Museum’s archive, which is currently being re-organisation, and I hope to post some gems from it in the coming months. Archiving my interaction with the museum is a priority too, as I investigate the museum’s online, digital and social media presence. I began mapping the museum’s website early on in my doctoral research; now that the museum has recently launched a new website there is a unique opportunity for assessing how changes in the museum’s offer are presented and communicated, and how the museum’s online presence might reflect and/or facilitate such changes.

In the process of change anomalies are revealed. On the museum’s newly-launched website, which is still in the process of being populated with content, I found that the Starck exhibition was listed as occurring in 1994, when in fact it was 1993. Cross-referencing with the previous website via a link, the comprehensive list of designers’ biographies, now labelled as the Design Library Archive, which looks to have been compiled from research for temporary exhibitions (as entries include images of exhibition installations and text from the exhibition scripts), does not include an entry on Starck despite. That in itself is odd as (noted in my review) the public’s interest in the star designer was cited by curators as impetus for the show. It’s doubly odd as the Design Library has also been cited as the most “visited” design resource in the UK; the curators were missing a golden opportunity to drive traffic to the site. Perhaps at some point an entry was removed, but only the data miners will ever know.

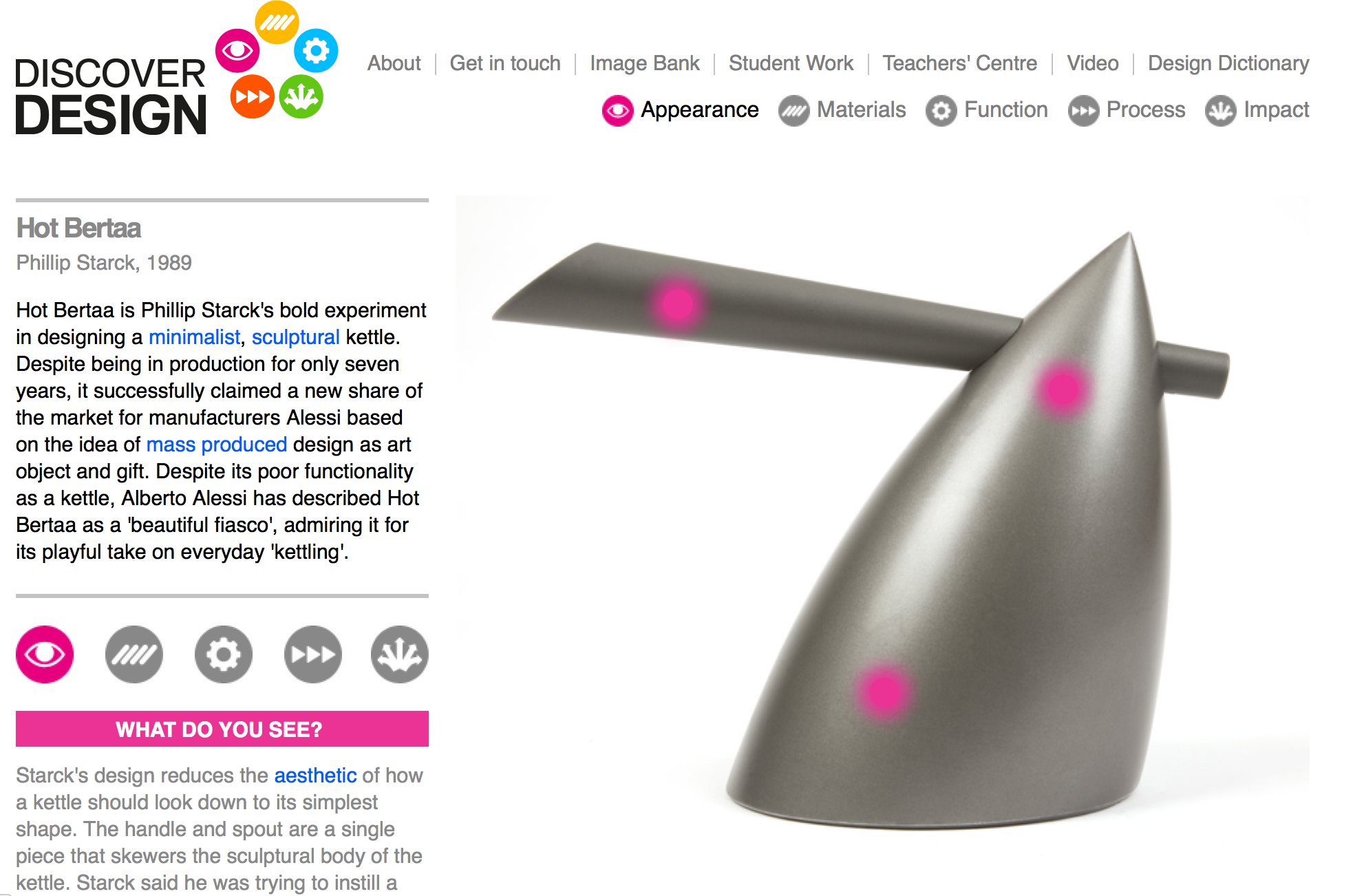

Starck is represented on the Design Museum’s new site though, or at least one of his iconic designs is; the Hot Bertaa kettle (1989) is used as a teaching aid, prompting students to question the “appearance” of objects. It can be found in the Teacher’s Centre, part of Discover Design, which is described as “an interactive online resource for primary and secondary teachers”. Unfortunately, Philippe’s name is incorrectly spelt; mistakes in such prominent place can have devastating effects and undermine credibility, as website visitors use what they consider to be an authoritative source to verify such details.

Starck’s iconic Hot Bertaa kettle for Alessi is used on the Design Museum’s Discover Design teaching resource

Finding traces of long-gone temporary exhibitions is another pre-occupation, and some images of the exhibition’s entrance and text panel may be found on graphic designer Norman Hathaway’s website. He worked on the exhibiton graphics and marketing material for the show and the images give a glimpse of a cool palette of materials, surfaces and san-serif type, which complements Starck’s more emphatic design language. For a comprehensive biography of Starck, check out his encyclopaedic company website. The Museum of Design in Plastics at the University of Bournemouth holds a number of plastic objects designed by Starck, with the website showing multiple views of each design, alongside information on the manufacturer, materials and production dates.

So, back to the days before the World Wide Web, when information about exhibitions was disseminated via printed leaflets and posters and reviews in newspapers and magazines included addresses and dates…

“Is Starck a Designer?”

Design Museum

Shad Thames, London SE1

June to October 1993

“Can Starck be serious?”

by Liz Farrelly

Design Review

Issue 9, volume 3, 1993, p. 14

Standfirst: London’s Design Museum has pulled off an international coup by putting together a collection of the unclassifiable Starck that fascinates, excites, but still keeps you guessing

The ambivalent sounding title of this exhibition and the in-your-face undesign of its publicity poster can’t disguise the Design Museum’s absolute joy at being the instigator of Starck’s first major museum (read non-selling) show. Only 18 months ago the curatorial staff, weary from replying to constant enquiries by student designers for information about Starck, struck on the idea of staging a comprehensive exposition of the enfant terrible’s 20-year career.

Such a spectacle would certainly be popular. But could the curators present a balanced evaluation of the maverick/icon, subject as he is to the “Lady Di Syndrome” – media build-up followed by unbridled backlash. Complications included Starck’s wish to design the installation, and his manufacturer clients’ (and possible sponsors) perception of London as “a bit of a backwater”. But Starck liked the idea of London and has been a fan of the Design Museum since his installation for the French Design exhibition caused a stir in 1989.

The resultant exhibition isn’t safe, but it is accessible. In one fell swoop the Design Museum is able to stem accusations of elitist programming and boost audience figures. The installation places objects at various heights on steel and wire-mesh “plinths”, so they protrude into a lowered ceiling of taut, white Lycra. Museologists may be horrified by the sight of semi-obscured exhibits, raised up to give viewers an unexpectedly intimate perspective. With the highest plinths supporting the smallest objects the visitor is looking from underneath, through the mesh.

Starck’s designs may seem familiar, but much of the audience will know them only as published two-dimensional images. Partly obscuring them emphasises their three-dimensionality.

The final version isn’t as radical as Starck intended. He describes this phase of his career as “ghost-like” – he’s most often sighted as a fleeting but omnipotent vision en route between client meetings. To reduce his designs to white ectoplasmic blobs Starck wanted the ceiling height to be only six feet four inches, completely sheathing the exhibits in Lycra. But the compromise is still impressive.

On show are more than 60 items: early prototypes, production pieces, this year’s launches and cast-aluminium architectural models (looking suspiciously like ashtrays), as well as an animated film, a video tour of Starck’s buildings and some free-hand sketches blown up and suspended behind the Lycra walls. The curatorial team of Paul Thompson, Director of the Design Museum, and Sue Andrew decided to show not only the most common Starck objects but also unrealised prototypes and ultra-new models.

The diverse selection includes tables and chairs (of course), Venetian glass vases, a prototype scooter, an “evil eye” lamp that changes colour and a mini-monolith computer hard disk. But through the plethora of objects appears a unique consistency of geometry, Starck’s curves, blobs, spikes, fins and wiggly sperm are all variations from a personal palette of forms which, over the years, he has explored, aligned and recombined. Another revelation is his use of a wide-range of materials: plastics, composites, metals, ceramic, leather and wood are often juxtaposed in unlikely combinations.

Whatever you think of Starck – whether he’s a visionary or just a stylist, a self-styled eccentric or a pioneer of 21st-century working methods, whether he has given design a bad name or helped to put it on the mainstream media’s agenda – this exhibition will undoubtedly keep you guessing further. The Design Museum has managed to pull of a coup on the international museum circuit and present the work of an unclassifiable character with suitable amounts of rigour and drama, which is altogether quite an achievement.

“Is Starck a Designer?”, Design Museum, Butlers Wharf, Shad Thames, London SE1. Until 3 October.